Energy Poverty: A Time Bomb Waiting to Be Defused

Energy poverty refers to the insecurity of persons, families or groups that do not have normal and regulated access, in their homes or in the places they live in, to energy sources necessary to meet their primary needs. The causes may be buildings poorly insulated against cold or heat or the price of energy resources. Energy poverty is responsible for climate problems and the ecological factor of the planet, as heating and operating the home is a direct and indirect source of significant greenhouse gas emissions, which can be reduced through energy efficiency. Energy poverty (also known as fuel poverty) was set out as concept, for the first time, in the UK, in 2001.

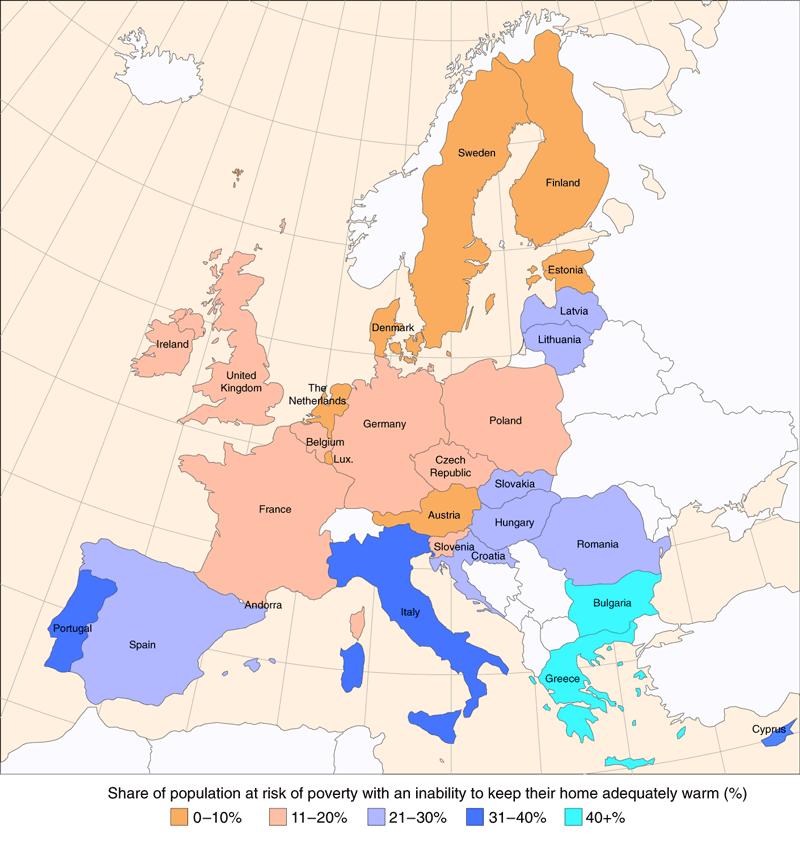

Energy poverty in Europe

According to Eurostat data, energy poverty (in the sense that the own home couldn’t be heated due to the lack of money) affected almost 7% of EU’s households in 2019. The seriousness of the situation varies widely from one country to another. The share of households with heating difficulties was the greatest in Bulgaria and Lithuania, i.e., 30.1% and 26.7% respectively. The share was above average in countries in southwestern Europe, such as Spain (7.5%) and Italy (11.1%). In France, it was 6.2% (slightly lower than the European average), while Germany (2.5%) and Finland (1.8%) were among the countries that managed to significantly diminish it. In general, single people, young people and single parent families are the most exposed to energy poverty. Across Europe, around one tenth of single parent families have hardly afforded adequate heating.

In Europe, during 2007-2019, electricity prices for household consumers increased constantly. The average cost per kilowatt-hour increased from EUR 0.18 in the first half of 2007 to EUR 0.21 in 2019, but with significant differences between the Member States. Denmark (EUR 0.31), Germany (EUR 0.30), Belgium (EUR 0.29), Ireland (EUR 0.25) and Spain (EUR 0.24) are the top five countries in which the kilowatt-hour is the most expensive, including all taxes and duties. At the other end, Member States where the kilowatt-hour is the cheapest are Bulgaria (EUR 0.10), Lithuania (EUR 0.10), Hungary (EUR 0.11), Romania (EUR 0.13), Malta (EUR 0.13) and Poland (EUR 0.13) (Eurostat).

Indicators used to measure energy poverty

Measurement of energy poverty requires a combined approach. This is what the EU Energy Poverty Observatory does, whose goal is to measure, monitor and inform about energy poverty. 28 indicators are used to assess the number of Europeans in energy poverty.

There are four main indicators, allowing to determine whether a household is in the situation of energy poverty. While two of these are based on statements regarding households’ access to energy services, the other two indicators assess energy expenses. In 2019, over 30 million Europeans felt they couldn’t maintain their homes properly heated, of which 6.2% represent the segment of those who cannot pay their duties on time: heating, electricity, gas, water etc. At the opposite side, 15.5% of European households allocate a large part of their income to energy expenses. It’s about the families living in buildings with low thermal and energy efficiency, which require more heating to obtain a comfortable temperature inside. Therefore, high income families have proportional energy expenses.

The need to address all dimensions of energy poverty

The EU Energy Poverty Observatory presents 24 secondary indicators that contribute to a better understanding of energy poverty, such as energy prices, number of power outages and the quality of housing.

Air conditioning and transport, underestimated elements of energy poverty

Although now the concept of energy poverty tends to focus on people who suffer from cold in their homes, energy poverty also exists during summer, as some families cannot maintain their houses cool enough. This ‘summer energy poverty’ is already a ‘life and death’ problem, as the 2003 heat wave in Europe reminds us, wave which caused 30,000 deaths. Climate change increases the frequency, intensity, and duration of heat waves, which leads to an increased demand for air conditioning, even in temperate climate zones. Research shows that social and economic factors play a major part in this phenomenon of excessive heat: the risk of exposure (poorly insulated housing), people’s capacity to react to excessive heat, as well as their sensitivity. Vulnerable members of a household, such as small children, the elderly and people with chronic medical conditions are particularly at risk. Therefore, summer energy poverty is an ever-increasing threat to the lives of people at a time when the European population is aging.

Also, many European dwellings have difficulties in accessing means of transport. The general concept of ‘transport poverty’ can mean the financial inability to travel, limited access or even lack of motorized transport or infrastructure. Therefore, transport poverty is not just the result of a significant financial burden related to fuel costs. Despite the diversity of causes and their consequences, there is a correlation between these various aspects of energy poverty. In some countries, poor quality of housing leads to thermal discomfort during winter and summer, and higher bills throughout the year. Another study underlines that many people could focus on transport expenses (to go to work reducing other expenses, for example high energy costs and consumption with the house).

Who suffers from energy poverty in Europe?

The main causes of energy performance of buildings (aggravated by the Covid-19 crisis) are given by the poor energy performance of buildings, high energy prices and low income of families.

The European building stock is characterized by a poor thermal quality of housing. Half of the buildings were built before 1970 and their energy performance is poor. In countries with mild winters (Portugal and Malta), where buildings were not designed for cold winters and whose energy efficiency is low (due to poor insulation), the situation is often uncomfortable for residents, especially in case of extreme temperature episodes, including during summer. There is a greater mortality during winter than in countries with cold winters, where buildings are more energy efficient.

In the EU, buildings are responsible for 40% of the EU’s energy consumption and 36% of the greenhouse gas emissions. According to the Buildings Performance Institute Europe, 97% of them need renovation to comply with energy efficiency standards and requirements for becoming buildings with close to zero emissions. However, energy renovation rates remain around 1% per year and only 0.2% of the buildings are subject to complete renovation every year (to reduce the energy consumption for buildings by at least 60%).

Link between energy poverty and low income

Households suffering from energy poverty are very often those with low income. Budget constraints limit their capacity to pay energy bills for the daily consumption and even more so to invest in rehabilitation for a long-term energy efficiency. Moreover, it is about housing where rents are more affordable, but energy costs are higher. However, energy poverty and income poverty do not overlap perfectly, as a low-income family can live in a well-insulated building and have reduced energy expenses. Therefore, the low income does not necessarily lead to energy poverty. If energy prices are high for the end-consumer, they can contribute to energy poverty. Therefore, for European families, electricity prices were corrected with inflation and increased due to politicians’ decisions of increasing electricity taxes. Energy poverty can be aggravated by such increase in energy prices, but it plays a much smaller role than the energy performance of housing and income.

Aggravating effect of the Covid-19 crisis

The measures taken by governments to stop the Covid-19 pandemic had a major impact on the European economy. Despite the mechanisms of partial unemployment established in EU countries, bankruptcy led to losses of permanent jobs and, therefore, an increase in unemployment in the EU. At the same time, lockdown measures forced to population to stay at home, which led to an increase in heating and electricity consumption and, therefore, higher energy bills, especially during winter. This could be a major impediment for many Europeans, especially for families that already have difficulties to pay their bills.

According to the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, in July 2020, 34% of respondents in Europe believed that their financial situations worsened with the pandemic and 44% said they were on the verge of not being able to keep their homes. Due to a decrease in income associated with an increase in energy expenses, more and more Europeans dedicate a higher share of their budget to fixed costs. Gradual increase in the number of persons benefiting from food aid is alarming. In France for example, food distribution increased by 30% between September 2019 and September 2020. This poverty affects students, temporary workers, but also the independent workers and handcrafters, which potentially increases the number and diversity of persons likely to suffer from energy poverty.

Women are more likely to be affected by energy poverty

Due to the longer life expectancy than in the case of men and due to lower pensions, older women face a particularly high risk of exposure to energy poverty. Single parent families are also very exposed, and they are represented by most single mothers (in 2019, 11% of adults with dependent children were single women, compared to 3% for men). Specialists’ study sheds light on the different ways of feeling and reacting to such poverty, depending on gender. Women must deal disproportionately with situations, especially in the way they experience or react to energy shortages (e.g., more effort to save energy, emotional stress to protect children etc.). Social housing and those whose rents are regulated by law are more affected by energy poverty, and families who rent are also affected: more than a fifth of EU tenants say they have difficulty heating their homes during winter and pay their bills. It is difficult for tenants to improve the energy efficiency of their homes, as homeowners may not be in favour of this. Families who own their own homes are, on average, less affected by energy poverty in the EU, but this hides major differences between Member States, especially related to differences in ownership in each state. In Romania and Hungary, over 90% of the homes are occupied by their owners.

Geographical and social energy fracture

Although winters are colder in northern Europe, the one that feeds energy poverty is southern Europe. This is what prompted some researchers to talk about a geographical and social ‘energy fracture’ that splits the EU in half and translates in the fact that a larger share of housing in the less developed Member States leads to the incapacity to meet basic energy needs. Bulgaria, Lithuania, Greece, Portugal, and Cyprus are the countries with the highest proportion of people who say they have difficulty maintaining an adequate temperature in their homes. This is explained not only by the high electricity and gas tariffs, but also by a higher risk of poverty. However, some countries where electricity prices are below average, such as Cyprus, Slovenia, Romania, Hungary, energy poverty is given in particular by the poor quality of housing. Moreover, absence of district heating and adequate heating systems leads to high energy expenses. This underlines the key role played by housing in energy poverty, which cannot be reduced to a form of monetary poverty.

Even in north-western Europe, energy poverty is a reality: according to Eurostat data, 3-4 million French and about 2 million Germans are not able to heat their homes properly. French people facing energy poverty show that these figures can be underestimated, as 14% of homes housing over 9 million people expressed a cold sensation during the winter of 2019-2020.

And yet, the number of EU households unable to heat their homes sufficiently fell from 9.5% in 2010 to 6.9% in 2019 (with a sharp decline in Bulgaria (-54.74%)).

Although data on air conditioning in Europe are limited, researchers have developed a European index of internal energy poverty which shows that most Member States have difficulties in winter rather than summer. These statistics are concentrated in the southern, south-eastern and Baltic Sea regions, where GDP per capita is often below the European average. In 2012, half of Bulgaria’s population said that housing was not cold enough in the summer, the same statement being true for 35% of Portuguese, Maltese, and Greeks. In contrast, less than 10% of the population was affected in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Sweden.

This European Energy Poverty Index also collects data on the share of energy expenses related to transport of low-income families. However, the data highlight significant differences that depend on the policies pursued in each country. Thus, Finnish and Irish policies have encouraged the construction of houses outside urban areas and access to public transport. For most low-income families in Hungary and Bulgaria, public transport is too expensive for regular use. In contrast, in Spain, Luxembourg and Cyprus, due to the price and affordability of public transport, it is a viable option for anyone.

According to a study conducted in France, 21% of families suffer from energy poverty in terms of transport. Meanwhile, the government estimates that 10.2% of families allocate an excessive share of their income to moving expenses.

Consequences of energy poverty

Financial consequences

Difficulties to pay the bills lead to the use of other budgets dedicated to equally important needs, such as housing, food, education; establishing mechanisms of restriction or even deprivation leading to other consequences; resorting to aid, with its humiliating nature and others through assistance mechanisms; debts with loan application.

Technical consequences

Heating restrictions have consequences on housing: the poorly heated house will be humid (the cold mainly affects the environment by reducing the air capacity to contain humidity); a poorly ventilated house will be humid and unhealthy and will deteriorate; it will allow the formation of mould and become conducive to unhealthy conditions.

Social consequences

Damaged or uncomfortable housing has social consequences, such as: feeling of injustice, difficult social life, difficult static activities (e.g., homework), difficulties in ensuring an adequate level of hygiene, deterioration of relations with the lessor/energy suppliers.

Health consequences

Lack of heat generates a few phenomena such as: fatigue; cold favours vasomotor reactions that can trigger the transmission of pathogens. Causal links have been demonstrated for several chronic pathologies (chronic bronchitis, osteoarthritis, anxiety and depression, headaches) and acute (colds and tonsillitis, flu, or gastroenteritis), but also symptoms such as wheezing, asthma attacks, hay fever, rhinorrhoea, or eye irritation.

Housing insecurity consequences

The use of oil or gas stoves can be the cause of fires, carbon monoxide poisoning.

Environmental consequences

Energy poverty and, in general, all homes with poor energy performance generate a great waste of energy and an increase in CO2 emissions.

Actions to fight energy poverty

Regarding energy transition, political decision-makers have a set of comprehensive political tools to move from a system based on the inefficient use of fossil fuels to a system based on the efficient use of renewable energy. The cost of this transition depends on the approach favoured by government policy: decision-makers can decide to increase fuel taxes or invest primarily in the renovation of buildings and public transport. The 2013 protests in Bulgaria highlighted political decision-makers who should bear in mind that a small increase in energy prices can have a major impact on the daily lives of millions of households already in financial difficulties. Therefore, a socially just transition based on measures aimed at improving the living conditions of the most vulnerable families is imperative.

In accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, the main public policies to combat energy poverty are pursued by Member States, regions, and local authorities. However, the European Commission (EC) has activated various instruments to support national and local action to lift Europeans out of energy insecurity: exchange of experiences, legislation, funds, and instruments, such as the recent ‘Renovation Wave’ strategy. By sharing the experience of energy poverty and informing policy makers launched in January 2018, the EU Energy Poverty Observatory (an EC initiative) was designed to assist Member States in their efforts to provide a platform for knowledge and good practice exchange. The combination of indicators provides a useful basis for collecting data and measuring the phenomenon at EU level. The data, results and research, experience gained on this platform are used by the EU Observatory to provide good practice, training, and advice to decision-makers.

At the same time, the Interreg Europe platform supports local and regional governments, sharing experiences in public policy and providing financial support for interregional projects. Thus, the Social Green project brought together municipalities and energy agencies from six Member States. It has made it possible to identify local policy instruments for greening the social housing sector. The results show that regions can learn from each other to face similar challenges. The EC is also considering launching an initiative to provide technical support for social housing projects. This project would involve the renovation of 100 flagship districts, which will be examples.

Legislative measures to encourage Member States to act

The Regulation on the Governance of the Energy Union provides that Member States are required to submit to the EC the national energy and climate plans and action plans for fulfilling energy and climate targets. These national plans should include an assessment of energy poverty and, if the number of households affected by energy poverty is estimated to be significant, the Member State should put in place appropriate measures to address the problem. In any case, assessment by the EC of national plans shows that several Member States do not pay enough attention to the problem, requiring a systematic approach to fight against energy poverty, instead of resorting to a unique action plan.

Examples of complex approaches to energy poverty

An analysis conducted by the EU Energy Poverty Observatory assesses to what extent national plans addressed energy poverty based on 13 criteria, such as recognition and definition of fuel poverty by the Member State or the type and number of measures presented to address this issue. The Belgian, Spanish, then French and Lithuanian national plans stand out as the ones with the most comprehensive approach to energy poverty, even if there are still gaps to be filled in their strategies. In contrast, several countries do not recognize or do not define energy poverty in their national plans and present a limited number of measures implemented. These countries are mainly those with a purely social approach. In 2019, less than 3% of the population of Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Netherlands, and Sweden said they are unable to heat their homes sufficiently. Moreover, these countries do not recognize, in their plans, in terms of energy and climate, energy poverty as a phenomenon. In addition, as part of the requirements of the Energy Performance Directive, Member States were required to submit to the Commission national long-term renovation strategies before March 2020; at the end of 2020, half of the states did not submit their strategies.

The EU also provides funding contributing to the fight against energy poverty, such as structural funds and European investment funds (ESI Fund). Under Horizon 2020 program, the EU has funded several research projects to test innovative solutions to fight energy poverty. Larger projects were supported by the European Investment Bank (EIB), through various activities. The European Local Energy Assistance Facility (ELENA, developed by the EIB and the EC) has been in operation since 2000 and has allocated EUR 180 million to energy efficiency projects in buildings and transport, mobilizing a total of EUR 6 billion in investment. This mechanism provides specialist assistance in setting up local projects, encourages large projects to reduce trading costs and to develop experiences that serve future projects. The EIB has also created a financial instrument, ‘Smart Finance for Smart Buildings’, which uses EU subsidies as collateral to encourage private investment in the renovation of residential buildings and helps 3.2 million households to come out of energy poverty. The EC also intends to strengthen access to private funding for building renovation as part of the future strategy. With the Covid-19 crisis, the EU has adopted a historic incentive package, the Next Generation EU (NGEU). This broad incentive package should allow the EU to act for the first time as a macroeconomic stabilizer.

EUR 312.5 billion out of the EUR 750 billion in the NGEU budget will be granted to Member States in the form of subsidies through a Recovery and Resilience Facility (RFF). Each Member State must submit a National Recovery and Resilience Plan, which must be approved by the EC before the State grants RFF funding to each Member State. In the 2021 Annual Strategy, the Commission launched a flagship initiative, ‘Renovate’, which presents the renovation of buildings as a priority in the RFF.

Political tools to address energy poverty

The European Pillar of Social Rights, proclaimed by the European institutions in 2017, enshrines a set of rights aimed at ensuring equal opportunities, fair working conditions and social protection for citizens. One of the 20 key principles is that everyone has the right to access essential quality services, including energy and transport.

The ‘Renovation Wave’ presented by the von der Leyen Commission should be a major discovery in the fight against energy poverty. It sets a framework for accelerating the overall renovation of buildings with poor energy efficiency in Europe and aims to renovate 35 million construction units by 2030. Published in October 2020, this strategy provides at least for doubling the renovation rate and improving the quality of renovation to reach higher energy efficiency standards. It seeks to remove obstacles to renovation, such as the difficulty of mobilizing funding and work organization, as well as the reluctance to engage in a lengthy process. The Commission identifies three priorities for renovation:

- Buildings whose energy performance is very poor

- Public buildings (schools can be relevant investment priorities during the recovery period)

- Decarbonization of heating and air conditioning systems

Based on the existing tools, the renovation wave proposes a comprehensive strategy based on legislation, directed funding and technical assistance tools. It also includes measures to make the building ecosystem more sustainable, to create environmentally friendly jobs, for worker training opportunities etc. At the same time, the EC has published a list of recommendations for Member States to fight against energy poverty. The Commission urges Member States to assess the redistributive effects of the energy transition, to use more means of public participation in the development of control policies against energy poverty, to improve coordination at different levels of government and to better identify low-income families.

Several energy poverty organizations (the Action Network, the ENGAGER COST action network, as well as national organizations) reviewed the measures implemented in six Central and Eastern European Member States and were not convinced of the effectiveness of the EU approach to energy poverty. The EU mainly provides directives to Member States, instead of providing real financial incentives for renovation or initiating coercive measures to push countries into action. The organizations conclude that if the responsibility for the fight against energy poverty lies mainly with the ‘goodwill’ of the states, the result will be limited, which requires more severe measures, but also incentives.

Conclusions

During winter, during the Covid-19 crisis and under the conditions of continuing lockdown measures, millions of Europeans must remain in poorly heated buildings. These circumstances worsen the situation of pre-existing energy poverty, creating more discomfort and worsening the health of at least 30 million Europeans. In the last decade, the EU has developed an action framework against energy efficiency, based on legislation, on exchange of good practices and funding tools to support vulnerable households and improve energy efficiency. The renovation wave is currently trying to accelerate the general renovation of buildings, an essential step in reducing energy poverty. Already using the tools in force and recent innovations in renovation, the European Union can from now on help all Europeans to step out of energy poverty. Such an objective would be politically desirable insofar as it would make it possible to expand the political coalition that supports the European Green Deal. Therefore, it could concretely improve the life and health of the millions of Europeans suffering from energy poverty. Therefore, this document claims that the EU and the Member States now need a political strategy based on a broad coalition and concrete intermediate goals, so that the goal of taking all Europeans out of energy poverty is the key to the European Green Deal.