Exclusive Economic Zone and the Energy Game: Waves in the Mediterranean

After many years of international disputes and reconciliation efforts, the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) introduced the concept of an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). This came along with the necessary technological advancements enabling the deep-sea exploration and the extraction of natural resources from the seabed. These developments, in turn, incentivized states to claim ownership over areas outside of their territorial waters, which is limited to 12 miles from their coasts.

Imaginary lines on the land and on maps have been drawn since the dawn of humanity to establish proprietary rights, sovereignty, rule or any kind of claim imaginable. This notion of drawing lines to claim land hasn’t changed till this day and a radical shift of paradigm is not to take place in the foreseeable future.

But what about the sea?

When it comes to sea borders, under international law, a coastal State does not have to make any declaration or take any formal action to establish a continental shelf as it belongs the automatically to the appurtenant state. The legal issue is in establishing borders, that is the delimitation of the continental shelf when there is an overlap between opposite or adjacent states.

The notion of Exclusive Economic Zone

Arvid Pardo, Malta’s ambassador at the time, really urged the UN to figure out a legislative frame for the drawing of lines on sea. More than a decade after that, on December 10, 1982, nearly 120 countries undersigned the new United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). According to UNCLOS, ships seeking passage through an Exclusive Economic Zone could navigate freely, but the sovereign state can reserve the right to defend its EEZ, protect it from environmental and other harm, and conduct any type of research within it.

EEZs currently represent a major source of dispute among sovereign states, especially when their Exclusive Economic Zone borders ‘touch’ or even worse when they overlap. It was a natural evolution but still a very young development and consequently there is not global status quo on how to unilaterally resolve this kind of differences. It is also only natural that states want to delimitate their maritime borders and increase their opportunities for its exploitation. It is also a necessity for security and environmental reasons, drawing clear lines of accountability for whatever happens in those waters included in an Exclusive Economic Zone.

The problems start when countries want to consider their Exclusive Economic Zone as purely maritime territory. It is not clearly defined when for example countries require fishing boats to ask permission before fishing in their EEZs. Some coastal states have taken extra steps and boarded ships with suspicious cargos, claiming security threats. While UNCLOS grants military ships immunity from being boarded or searched, it does not clarify the status of EEZs in this regard. The United States interprets EEZs as having purely economic implications whereas China and other states, interpret EEZs as granting them rightful permission to manage all activities within their territory, including the military type. This has created major disputes for one of the biggest geopolitical challenges of our times: The South China Sea contention.

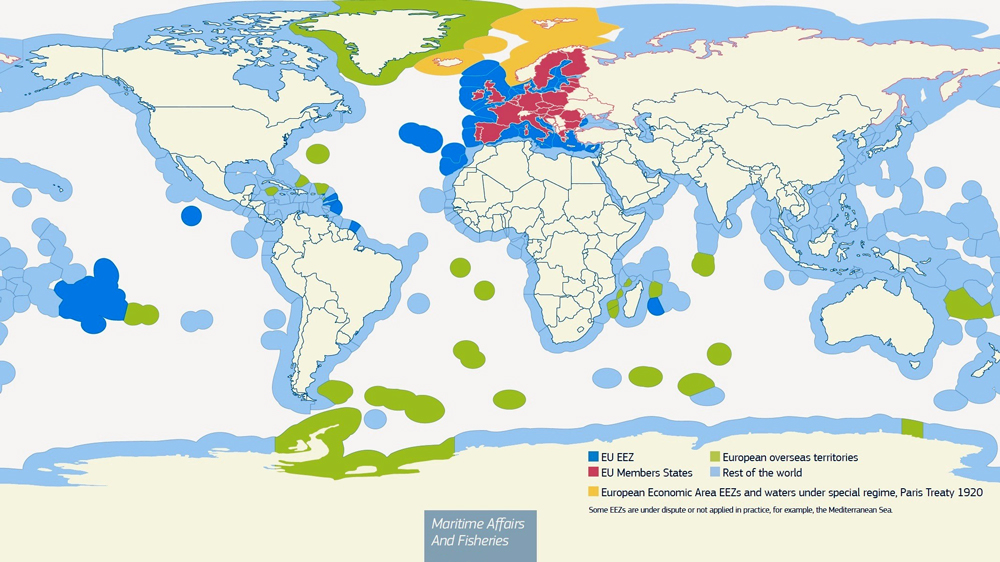

States can, but do not have to, declare their EEZs. To delineate an Exclusive Economic Zone, a state must pass a specific law that clearly defines its Exclusive Economic Zone and the procedures for navigation within it, and submit it after to the UN – without seeking approval. By 2016, more than 137 countries had claimed 200‑mile EEZs. Obviously, this works better for states that are not in too crowded regions: like Australia or the US. That changes when we even think to apply it in the Mediterranean for example.

The countries of the Mediterranean that could potentially benefit most from an EEZ declaration are Greece, Cyprus, Italy, and Malta. As its name suggests, an Exclusive Economic Zone grants a sovereign state the rights to exploit and use natural resources in the sea, on the seabed, and underground. This is where it starts getting very interesting and the implications are very straightforward for the Energy sector. The coastal State has absolute authority to drive and oversee any activities related to exploration and exploitation of living (and not) resources, which would naturally include offshore oil and gas resources. Also, the owner of the Exclusive Economic Zone has absolute jurisdiction to authorize offshore structures for exploitation of offshore oil and gas resources.

The Mediterranean dimension

Especially for the Mediterranean, a major source of dispute, are the status of islands. The UNCLOS established that an ‘archipelago’ “refers to a group of islands and interconnecting waters that are closely interrelated and form an intrinsic geographical, political, and economic entity”. The curious thing is that many claim that, in the Mediterranean, only the Maltese islands qualify for this definition. The same definition is an obstacle for Greece, who owns all but two of the islands in the Aegean. Let’s also not forget that since there is no sea area longer than roughly 400nms in the Mediterranean, if all states claimed their full 200nm EEZs there would be not enough sea to cover.

Given the Mediterranean’s relatively small size, if all Mediterranean coastal states declared their EEZs, those EEZs would span the sea in its entirety. Most coastal states have avoided such a declaration; according to UNCLOS, when EEZs overlap (which is the case in the Mediterranean), states are required to engage in arbitration with neighbouring states and, in effect, give up part of their claims. Some Mediterranean states have therefore preferred not to declare their EEZs to avoid giving up territory and raising tension with neighbouring countries. Greece, for example, has not declared its Exclusive Economic Zone, because in doing so Turkey would be left with almost no Exclusive Economic Zone of its own in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Of course, this is where Turkey enters the game, as the most notorious player in the region. The EEZ of Greece is of course a problem for Turkey and it actively tries to dispute/annex parts of it. Greece treats its islands in accordance with UNCLOS and seeks to implement a territorial water zone of 12nms, which would be a substantial fraction of the Aegean Sea. Turkey is only willing to accept a Greek territorial water zone half of it. Turkey has proclaimed that if Greece extends its territorial zone, there will be war (casus beli).

On the other hand, and in a much braver manner, in 2004 small Cyprus declared its Exclusive Economic Zone. The government of Greece naturally hailed the initiative without doing the same thing. Turkey of course, did not appreciate that either and intervened, sending naval military units in Cypru’s waters. Cyprus registered to the International Court in The Hague after the Turkish embassy in Athens refused to officially receive Nicosia’s protest against the exploration and exploration operations carried out by Ankara within Cyprus’s EEZ.

Another interesting example of the region is Israel. Despite being one of the signatories to the 1958 United Nations Convention on the Continental Shelf, Israel has not signed UNCLOS. Nevertheless, Israel has delimited its territorial waters and Exclusive Economic Zone in the Mediterranean through direct agreement with Cyprus, in accordance with the international laws. Among Israel’s official reasons for not signing UNCLOS is Article concerning settlement of disputes, which could obligate Israel to abide by the mandatory procedures of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, where they would have no control and maybe that would weaken their claims for the surface they claim.

Athens, Ankara, Tripoli and… Tripolitania?

Nowadays almost every coastal country is taking action towards creating EEZs and this would not be an exception for the very trafficked Mediterranean, thus challenging unspoken power equilibriums, and forcing future alliances and (hopefully not) conflicts.

Greece’s role in the Mediterranean Energy game, and even more regarding the delimitation of EEZs, is integral due to its geographical position but also due to the proximity with Turkey – the most aggressive player on the regional table. The very concept of a European ‘EEZ Policy’ is a very important one and for Greece it only makes sense to aggressively pursue its establishment. That would offer Greece (which has shown historically to be surrendering to Turkey’s aggression) much needed leverage to push back. A potential joint declaration of EU Exclusive Economic Zone in the Mediterranean would reduce the potential of Turkey declaring war.

Normally, EEZs should have been established without major disputes by now, but Turkey has its own opinion (and apparently the means to enforce it) over how the lines should be drawn. Most specifically, the Turks have strong opinions of how Greece’s lines must be drawn. The delimitation of a Greek EEZ with its neighbouring countries, except Turkey, was until now a fairly easy task. With Cyprus, the delimitation had positive results for both countries, since they will be using the equidistance method.

With Albania, it seemed simple but got eventually complicated. Actually, an agreement has already been signed, and then cancelled by the Albanians (presumably after Turkish incentivization). The delimitation of the maritime zones between Greece and Albania took place in 2009 using the median line (equidistance) method and the outcome was called a ‘multipurpose maritime limit’ – not EEZ – because Greece had not declared yet an EEZ due to the Turkish factor. Eventually, even if Albania has accepted Greece’s the deal, and only a trilateral deal was remaining between the two and Italy the Supreme Court of Albania declared illegal this agreement after the presumed interference of Turkey.

On another note, the delimitation with Egypt really started with the wrong foot as the Greeks tried to discuss with the Egyptian government, which had an absolutely pro-Turkish policy, in 2009. Greece was almost humiliated by the Egyptians when they were informed that Egypt would also discuss with Turkey, on their common maritime borders – even if according to Greece and Cyprus Egypt and Turkey’s EEZs would be adjacent. Egypt could only have a maritime border with Turkey only if the rights of the Greek islands of Kastelorizo and Stroggyli are not recognized. Apparently, these geopolitical games are purely political, as lately the equilibrium has changed. The current Egyptian government, furious at Turkey for its interference in internal matters during the Arab spring, is much more eager to settle the matter with Greece. This will facilitate delimitation of Cyprus’s common borders with Egypt.

On its western side, Greece signed an agreement with Italy on maritime boundaries on June 9, delimiting an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) between them, ending a 40-year long matter. Charles Ellinas, a senior executive at the Global Energy Center at the Atlantic Council, stated that: “This is the first step. The next to follow should be EEZ delineation agreements with Egypt and Cyprus,” and that “Greece must first declare its complete EEZ before it can enter into any future, meaningful, negotiations to resolve East Med maritime disputes.” Italy and Greece have already partnered in the EastMed gas pipeline to transport gas from Israel and Cyprus to Greece, Italy and other European countries. Ellinas also argued that “Turkey cannot enforce its distorted interpretation of international maritime law, on which its MoU with Libya is based, merely through force. The basis of agreeing EEZs and continental shelves must be UNCLOS, the UN law of the seas, which is now accepted international customary law. The two countries agreed on December 1 to accelerate the process of delineating their EEZs – now is the time to do just that”.

On the Southern side, and regarding the delimitation of the EEZ between Libya and Greece, there have been challenges in the past but recently these challenges have been escalated to major disputes as Libya (a part of it, since the country is in civil war) has signed a memorandum with Turkey (not surprisingly) which states that they have common sea borders, overruling Greece’s sovereignty over the Aegean and just dismissing Crete as a whole.

But in order to understand this problem, we might want to take a look at Turkey’s position on the matter. Turkey has one of the longest coastlines in the Mediterranean and its main line on the subject is that the islands lying on the “wrong side of the median line between two main lands” cannot create maritime. Therefore, and in simpler words, even of all the islands of the Aegean belong to Greece, Turkey’s position is that if we cut Aegean in the middle, the islands closest to Turkey do not count for establishing any territorial claims for Greece.

In September 2019, Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan manifested officially Turkey’s claims, revealing his own special vision and more specifically the new borders of Turkey with a ‘Blue Motherland’ map. In November 2019, Turkey eventually submitted a proclamation to the United Nations presenting their ‘Blue Motherland’ idea. Of course, the idea itself was to force Greece to share its own Blue from the Aegean so the Turkish motherland could become Bluer.

Later in, 2019 Turkey’s defence minister Akar published maps with Turkey and Libya having common maritime borders, dismissing the fact that there are enormous (Crete) and smaller Greek islands in the middle. The agreement was signed between Tayyip Erdogan and Fayez al-Serraj, the head of the Tripoli-based government (or Tripolitania’s government, as it is also referred) which Ankara is supporting militarily in Libya’s civil war. This agreement creates a joint maritime strip extending across the Eastern Mediterranean from the south-eastern Turkish coast to the north-eastern Libyan coast, in the waters between Crete and Cyprus, north of the Egyptian coast. This move, after the initial awkward moments, has obviously produced strong reactions from Greece, Cyprus, and Egypt.

Nevertheless, the agreement was denounced by the Government of East Libya led by General Hafter. Hafter and al-Serraj are leading the two opposite sides in the Libyan civil war. Certainly, Turkey has recently granted to al-Sarraj a very ‘generous’ loan of 2.7 billion US dollars. Additionally, Turkey has already deployed thousands of trained guerillas, from the Syrian, front in Libya in support of al-Sarraj’s regime; it is also claimed that those guerillas are also reinforced by Turkish tactical forces and certainly equipment and supplies. The truth is that even if Turkey’s involvement was a clear violation of every international law, the UN eventually backed al-Sarraj (who controls only Tripolitania) against Hafter who controls the rest of the country.

“With this new agreement between Turkey and Libya, we can hold joint exploration operations in these exclusive economic zones that we determined. There is no problem,” Erdogan said. “Other international actors cannot carry out exploration operations in these areas Turkey drew (up) this accord without getting permission. Greek Cyprus, Egypt, Greece and Israel cannot establish a gas transmission line without first getting permission from Turkey,” he added.

The Energy implications

When it comes to an EEZ, the sovereign coastal State can exercise all rights on the body of water for exploitation all-natural resources, from fishing to the extraction of oil, gas or other resources.

The new agreement between Turkey and Libya apparently complicates multiple plans and projections for Energy projects in the region. Turkey’s claimed EEZ carves out a corridor between Cyprus and Greece which is supposed to contain the planned gas pipeline from Israel. Turkey’s move defies the sovereignty and claims of Greece, Egypt and Cyprus and in fact annexes them. If Turkey wants to enforce its proclamation, it would actually mean that they can stop, board and control all vessels seeking passage through this corridor. Obviously, Turkey chose to flex its military muscles in the Eastern Mediterranean with the Turkish navy’s presence increasing since 2008. Turkey is also using two seismic and another two drilling vessels to search for natural gas, dispatched to disputed zones with Greece and Cyprus, demonstrating its power to force developments.

Italy is also very cautious about the issue of the Turkish-Libyan Exclusive Economic Zone. However, at the Cairo Summit held on January 8 last, Italy declared null and void the claims of Turkey and Tripolitania to oppose the claims of Greece, Cyprus and France. Italy apparently is concerned with Turkey’s excessive aggression, while France well protects the investments of Total and hence also the agreement between Total and Eni. Italy’s energy policy, which was never very supportive of the EastMed project, favours the Green stream pipeline from the Libyan/Tunisian coasts. The fact that potentially huge gas fields have been discovered in the waters around Cyprus, has enormously increased the stakes of the Energy game in the Mediterranean; if you add Turkey’s aggressive policies in that equation, the you get a very explosive mix.

Meanwhile, the East-Med Gas Forum managed so far to improve and reconcile relations between Greece, Cyprus, Israel and Egypt. The conclusions though are not being enforce in the same way Turkey enforces their proclamations for potential EEZ. It has also necessary to mention that Turkey has not yet proclaimed its own EEZ, except for the one defined between Turkey and the pseudo-State of the Turkish Cypriot Republic, and it accepts the proposal of EEZ with al-Sarraj.

On another note, Israel has defined its EEZ by excluding the sea in front of the Gaza strip, integrating its lines with those of Cyprus and Greece. Almost all of Israel’s trade is conducted by sea, making Turkey’s aggressive proclamations a challenge. On December 2019, a Turkish navy ship prevented an Israeli research ship from proceeding to underwater research operations in Cyprus’ EEZ, even if Cyprus had approved it. The Turkish warship demanded that the Israeli ship abandon its operations and withdraw from the ‘Turkish EEZ’.

Moreover, in October 2019, Turkey started its oil and gas exploration in Block 7, which is part of the Cypriot EEZ and to be jointly exploited by Total and Eni. The French company, Total, was given 20% of the Cypriot Blocks 2, 30% of Block 3 and also 40% of Block 8, previously totally in Eni’s hands. On June 2018 Eni discovered a large Egyptian underwater field (Noor) which is already considered to be the most important in the Mediterranean and could radically change Egypt’s economy and power projection. Therefore, Turkey is trying to tighten its military presence and grip of the sea around Cyprus in order to enforce its own status quo. Blue Stream, South Caucasus Pipeline, Southern Gas Corridor, TANAP and the Turkish Stream are all efforts manifesting Erdogan’s fantasies for regional hegemony.

Conclusion

Eventually, a notion that has been created to ensure stability, security and promote prosperity can be turned around and used as a weapon in the hands of any ill-intentioned user. EEZs have been a key and will continue contributing to maritime security and it will eventually help states settle their disputes; it seems to be rather a catalyst than a problem itself.

In the Mediterranean, and especially in the Eastern part, the EEZ notion has given fuel to the fire of aggressive claims from some of the regional players, namely Turkey. The truth is though, that these disputes would manifest one way or another, sooner or later.

The real question remains: are the countries of the region willing to resolve effectively their disputes and prosper or prosperity will have to be sacrificed on the altar of indecisiveness and fragmentation?