Need for Rapid Pivot to Gas

International energy consultancy Xodus Group has launched new analysis showing that a rapid pivot to gas will be required to deal with rising global energy demand.

In contrast to some recent future energy scenarios, Xodus believes worldwide energy consumption will continue to increase, driven by economic growth in developing countries, and that approximately half of that demand will need to be fulfilled by natural gas.

The ‘Rapid Pivot to Gas’ report by Xodus’ Advisory team, demonstrates that under this model, approximately USD 20 trillion would need to be spent on natural gas exploration and production over the next 20 years. The forecast would require significant advancements in technology to produce the gas responsibly, including carbon capture and storage (CCS) of the carbon dioxide produced. The scenario includes the phasing out of coal and oil in response to vehicle electrification and environmental pressures and a rapid and robust increase in renewable production.

“Recent forecasts take a developed world view showing either a plateauing or fall in energy consumption, but growing populations in developing countries mixed with increasing wealth are much more likely to result in a surge of overall primary energy consumption. We are anticipating an unprecedented decline in oil and coal, but even with energy from renewables modelled to the most aggressive increase, our analysis shows that a much more rapid pivot to gas is required to meet increased demand. Securing that gas sustainably by quickly enabling CCS and other decarbonisation technologies must move further up the agenda of governments and industries around the world,” Andrew Sewell, Director of Subsurface at Xodus Group said.

The report shows that over the past 25 years, per capita energy consumption of developing countries out with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has grown at just over 2.0% annually. In the OECD, on average per capita consumption has fallen by about 0.2% annually in the same period. These growth rates were used to project future energy demand by region. The UN projects the OECD population to grow from 1.3 billion people in 2018 to around 1.4 billion people in 2040, whereas the non-OECD population grows from 6.3 billion in 2018 to 7.8 billion in 2040.

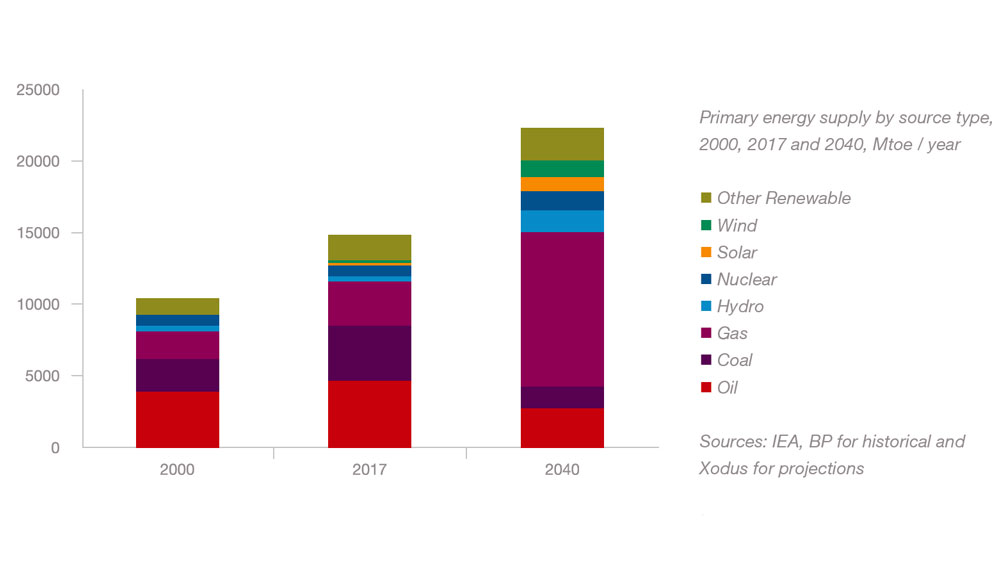

Based on these numbers, the overall primary energy consumption will surge from 14,300 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) per year to 21,500 Mtoe per year in 2040, presenting a challenging supply and demand scenario.

Xodus predicts that crude oil and coal will decline to 1,500 Mtoe per year and 1,200 Mtoe per year respectively by 2040. Unconventional oil and other liquids are projected to increase over the entire period as is nuclear energy, assuming no major changes in policies. Aggressive growth rates have been assumed for renewables, particularly wind and solar at over 1000% each by 2040. In addition to sustained installation capacity, the uptime and efficiency of new capacity is projected to keep improving for the next 20 years.

“Assuming that natural gas supplies the difference in total demand, we estimate that consumption could grow up to 200% by 2040 accounting for half of all primary energy consumption and 73% of the fossil fuel component. Energy industries need to consider this potential gas demand spike in the landscape of the necessary decarbonisation of our global energy supply along with the huge exploration and production expenditure it would require,” Andrew Sewell added.

Xodus advises on business transactions in excess of USD 10 billion each year. Advisory experts are involved in reserves audits, revenue projections, capital requirements, asset integrity and decommissioning liabilities and they regularly work with banks, private equity firms and oil and gas operators. The team has recently advised on deals including North Sea and Middle East infrastructure investments, North Sea and West Africa asset investments, and a North Africa project finance.

Background

Much has been made of the world’s primary energy transitions, from wood to coal to oil, interspersed with an aborted switch to nuclear, and now to natural gas as a waystation to renewables and perhaps hydrogen.

The drive for the current transition is the impact on climate from CO2 emissions, rather than any immediate lack of oil or coal reserves. The pivot to gas will be a forced choice for want of an alternative that can provide cleaner energy at the volume required to sustain a growing world population with an increasing per capita energy demand. Energy efficiency can and will help, but absolute declines in energy demand are very rare and typically related to severe economic setbacks. The last such occurrence was around 2008-2010. It is important to be clear that electricity is not a primary energy source, electricity is generated from primary energy sources and is essentially a medium for distributing that energy.

Total energy use

There are two main drivers for more energy: a) there are more people on the planet, and b) increasing wealth.

The latest United Nations (UN) estimate of human population is 7.7 billion in 2019, up from 6.1 billion in 2000. The UN expects further growth to 9.2 billion by 2040. Most of the additional people will be in Africa and Asia, while Europe is projected to see its population fall.

Xodus projection of primary energy demand is based on these UN projections of the development of the human population and a trend extrapolation of per capita primary energy use. The trend extrapolation is split into OECD and non-OECD countries, reflecting the world’s wealth disparity and propensity to consume. Over the past 25 years, on average non-OECD per capita primary energy consumption has grown at just over 2.0% annually. In the OECD, on average, per capita consumption has fallen by about 0.2% annually in the same period. These growth rates have been used to project future primary energy demand by region.

Under this projection, the absolute numbers increase from 1.3 Mtoe/capita in the non-OECD in 2018 to 2.0 Mtoe/capita in 2040. In the OECD, per capita consumption declines from 4.4 Mtoe/capita to 4.1 Mtoe/capita. This level for the OECD was last observed in the 1970s. Global average Mtoe/capita consumption grows from 1.8 to 2.35 Mtoe/capita by 2040.

This is a direct consequence of the changing population mix. The UN projects the OECD population to grow from 1.3 billion people in 2018 to just short of 1.4 billion people in 2040, whereas the non-OECD population grows from 6.3 billion in 2018 to 7.8 billion in 2040.

Based on these numbers, the overall primary energy consumption will surge from 14,300 Mtoe/year in 2018 to 21,500 Mtoe/year in 2040. As the non-OECD countries becomes wealthier, enabled by increased access to energy, their consumption increases from 8,200 Mtoe/year to 15,800 Mtoe, whereas the OECD only increases marginally from 5,600 Mtoe/year to 5,700 Mtoe. The effects of the larger number of people in the non-OECD easily offsets the efforts undertaken in the OECD to become more efficient. To radically lower global consumption would therefore require a significant reduction in the already low energy demand per capita in non-OECD countries, which would in turn imply limited economic growth and therefore prosperity.

Energy mix

The starting point for Xodus projection of how a rapid pivot to gas might occur starts with a decline in coal consumption for environmental reasons, and an unprecedented reduction in oil (liquid hydrocarbons) consumption as transport and other major users rapidly convert to electricity produced from alternative primary sources of energy.

They postulate that conventional crude oil and coal could decline to 1,500 Mtoe/year and 1,200 Mtoe/year respectively by 2040. This is 56% and 68% below 2018 levels. Unconventional oil and other liquids such as NGL’s are projected to increase over the entire period and reach 1,325 Mtoe/year. Nuclear energy is projected to increase by 2.5% per year, to reach 1,200 Mtoe/year, assuming no major change in policies and public perception take place. And even if there was a substantial move back to nuclear, then the time required to plan, approve, build and commission new nuclear stations will mean no significant change in nuclear supply over the next 20 years. The same applies to any breakthrough in nuclear fusion that may occur.

Hydroelectricity is expected to continue to grow slowly and reach 1,585 Mtoe/year.

Aggressive growth rates have been assumed for renewables, in particular for wind and solar. In addition to sustained installation of capacity, the uptime and efficiency of new capacity is projected to keep improving for the next 20 years, so that net energy delivered per unit of capacity.

Xodus has assumed that natural gas supplies the difference between the total demand and the sum of other sources described above; the gap filler so to speak. Natural gas consumption is estimated to have been around 3,800 Mtoe/year in 2018. In this projection, consumption is set to grow 2.5 times by 2040 to some 10,000 Mtoe, accounting for 50% of all primary energy consumption and 73% of the fossil fuel component.

When thinking about sources of primary energy, it is not a question of either/or, it is a question of what can reach scale fast enough to meet continued demand growth.

The overall share of natural gas rises to 50%, while coal drops to 6% and oil to 13%. Fossil fuels combined drop to 69%, down from 81% in 2017. Solar and Wind increase to 4% and 5% of total primary energy supply, up from 0.5% and 0.7% respectively in 2017.

Growing natural gas threefold in just over 20 years looks like an impossible task. But there are historical precedents regarding energy supply over the past 150-200 years. From the perspective of someone in 1945, the subsequent roll-out of the oil industry would have appeared equally as unlikely as the natural gas roll-out described here appears to us today. Yet, in just over 15 years, global oil production tripled from 350 Mtoe/year, and then tripled again from 1,000 Mtoe/year to 3,000 Mtoe/year between 1960 and the mid-1970s.

While the circumstances of the oil industry in the 1950s and 1960s are clearly different to the natural gas industry today, there is already a large natural gas industry in place today which provides a solid base for expansion, and recent years have shown that dramatic improvements in productivity per well can be made as new technologies are brought to bear.

Renewables, including wind and solar in particular, provide a considerable portion of new energy sources. The growth levels assumed by Xodus for these energy sources will also be a challenge. Their use is geared to power generation, and while substantial electrification is anticipated, other media for delivering energy are required by different industries. In addition, the nature of wind and solar means they are an intermittent energy source.

Back-up capacity from other energy sources remains a requirement until such time as electricity storage on a huge scale is possible. Insofar as existing back-up excess capacity exists, the marginal cost of maintaining that to support renewable energy generation will be moderate.

However, if and when back-up capacity needs to be constructed specifically to support renewables, the costs should be integrally added to the renewables cost.

Energy forecasts comparisons

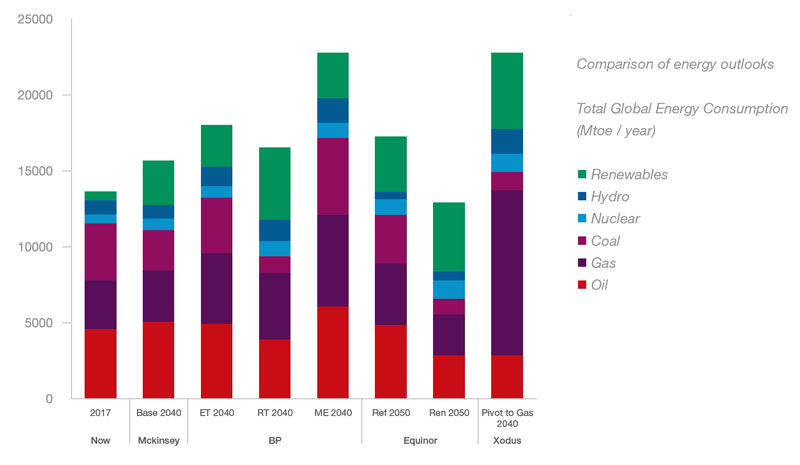

The overall energy demand Xodus proposes is higher than most scenarios envisage, but in agreement with the overall demand posited by BP in the ‘More Energy’ (ME) scenario in their 2019 outlook.

This gives a figure of 22,600 Mtoe/year, which is approximately 30% more than most of the scenarios described by a range of oil companies and agencies. The qualitative rationale for this higher figure is that the under-developed parts of the world will be moving towards what we might call a European middle-class standard of living and energy consumption. This process is already advanced in China and underway in India, but there remain parts of the world, notably sub-Saharan Africa, where the process has barely started.

Looking at some of the other forecasts, the McKinsey view assumes a rapid global electrification takes place leading to large efficiency gains and therefore lower total energy demand. Gas plays a small part with the current increase tapering off. Renewables increase substantially, although not as much as in Xodus view. Oil demand is broadly a ‘mid-case’ compared to the other energy views provided.

The McKinsey view is similar to the BP ‘Rapid Transition’ view albeit the BP RT view assumes larger total energy demand, a larger role for gas and a much larger increase in renewables largely at the expense of coal. The BP ‘Evolving Transition’ (ET) represents BP’s mid-case in terms of total energy demand in between the ‘Rapid Transition’ (RT) and ‘More Energy’ (ME) views.

Equinor provides forecasts up to 2050. The ‘Renewal’ (Ren) forecast is what needs to happen to limit global temperature increase to 2°C, assuming no technology implemented to scrub, capture and store CO2, and would be viewed by most commentators as an unlikely scenario. It requires oil and coal demand to be now in decline, with gas peaking around 2030. The ‘Reform’ (Ref) view is akin to BP’s ‘Evolving Transition’ scenario in terms of both motivation and macroeconomic factors and indeed produces a not too dissimilar total energy demand and mix.

Gas resource

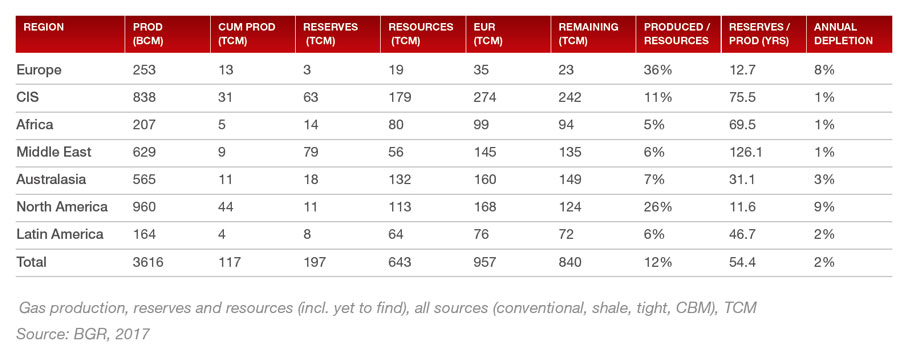

Clearly this ‘Pivot to Gas’ view relies on sufficient gas being available, cheap and accessible. Gas production is generally considered to be without resource constraints at the global level.

According to the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources (BGR), cumulative historical gas production is about 120 Tcm, which is 13% of the current estimate of ultimately recoverable gas of 957 Tcm, including unconventional and undiscovered resource. These numbers are comparable with estimates from other organizations such as IEA, Cedigaz and BP. This global recoverable resource would take 54 years to deplete at current production levels. The regions with the highest remaining recoverable resource are Russia, the Middle East and Africa.

Therefore, there are no immediate concerns about availability of natural gas, although significant exploration and development expense and effort will be required to convert all these resources to reserves. What is different though from earlier energy transitions, is that to all intents and purposes, global conventional oil production is plateauing.

Current global depletion of oil stands at over 35% of estimated recoverable resources (BGR, 2017). Oil consumption is also under attack from a political angle, making new oil investments riskier. Whatever is in the ground will ultimately matter less than the appetite for investment. Oil’s demise is likely to be a combination of the economics of producing the remaining in-ground resources and the general desire to leave the oil era behind us.

Notwithstanding these incentives, there will be prolonged and sustained liquids production. Likewise, coal is seen as a polluting fuel and its use is fiercely discouraged. While market movements may favour coal, regulation will hamper continued use.

Given that coal, oil and natural gas are currently the three main sources of primary energy, the pivot to gas takes place in a unique environment where the two key alternatives to natural gas are subject to stalling or falling demand. It is therefore not just demand growth that natural gas will have to satisfy, but also the reduction in supply of oil and coal.

Part of the replacement will come from renewable sources, such as wind and solar. But, despite the expected huge growth in these, they are unlikely to be able to plug the gaps of falling output and increasing demand by themselves.

This is particularly the case while conventional capacity is required to step in when wind or solar are unable to produce electricity as a result of their intermittency.

Conclusion

Energy demand will increase significantly over the next 20 years, driven by growth in primary energy per capita and population in non-OECD countries.

In order to grow their economies and generate wealth, these countries will need to intensify their development towards energy prosperity that the Western world began over 200 years ago. Renewables will help reduce the fossil fuel intensity of this growth, but the majority will need to come from fossil fuels. Natural gas can provide ideal support for electrification with high energy density, wide availability, affordability and being ‘cleaner’ than oil or coal. Gas therefore should be the likely energy source to fulfil this increase in demand. Carbon Dioxide emissions produced from burning this natural gas will increase and in order to even get close to some of the Paris Agreement targets, these emissions will need to be stored via CCS (or similar) technologies.

While the mix of primary energy sources in Xodus ‘pivot to gas’ view is one of many possible scenarios, a large increase in overall primary energy demand forecast is highly likely. To meet this, there will need to be significant growth in the supply of natural gas. Whether this is double or treble current levels is up for debate, but the requirement for the E&P industry to adjust to ‘more gas’ is not.