Submarine Cables: Risks and Security Threats

99% of the internet network runs through submarine cables. It is estimated that over USD 10,000 billion in financial transactions run today through these “seabed highways”. This is especially the case of the main global financial exchange system, SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications), which has recently been banned for many Russian banks. The security of these transactions is a political, economic, and social problem. This is a major issue that has long been ignored. The extreme geographic concentration of the cables makes them particularly vulnerable. There are over 420 submarine lines in the world, totalling 1.3 million kilometres, over three times the distance from Earth to Moon. Record: 39,000 kilometres length for the SEA-ME-WE 3 cable, which links South-East Asia to Western Europe through the Red Sea.

Submarine internet cables have a crucial importance, like oil and gas pipelines. In the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the seabed is more than ever a battlefield that must be protected. Western armed forces are considering a nightmare scenario of total interruption of the Internet in Europe, as 99% of the global network runs through submarine cables.

Satellites account for only 1% of data exchanges. The reason is simple: they cost more than cables and are infinitely slower.

A hundred submarine cable breaks a year

These infrastructures are equally important today as oil and gas pipelines. But are they equally protected? Modern submarine cables use fibre-optic to transmit data with the speed of light. However, while in the near vicinity of the shore, cables are generally reinforced, the average diameter of a subsea cable is not much larger than that of a garden hose.

For several years, the major powers are fighting a “hybrid war”, half open, half secret, for the control of these cables. As Europe focuses increasingly more on threats to cybersecurity, investments in the security and resilience of physical infrastructure that are the basis of its communications with the world does not seem to be a priority today.

The fear to act will only generate the vulnerability of these espionage systems, interruptions of data flows and undermining the security of the continent. On average, there are over a hundred breaks of submarine cables every year, caused in general by the fishing boats that pull the anchors. It is difficult to measure intentional attacks, but the movements of some ships have started to draw attention since 2014, their route following submarine telecommunication cables.

The first attacks of the modern age date back in 2017: it is about the cables between the UK and the US and between France and US. Although these attacks remain unknown to the general public, they are no less worrying and prove the capacity of external powers to separate Europe from the rest of the world. In 2007, Vietnamese fishermen cut a subsea cable to recover composite materials and try to resell them. Vietnam lost this way almost 90% of connectivity with the rest of the world for a period of three weeks.

Potential risks

Creating a European program to increase EU’s capabilities to prevent attacks on this infrastructure and repair the damages that they could cause is more urgent than ever. Russian “fishing” or “oceanographic” vessels and which are, generally, collectors of information, are increasingly traversing the coasts of France and Ireland through which these “information highways” pass. Yantar, an “oceanographic” vessel that has an AS-37 mini-submarine, was able to submerge in August 2021 to a depth of 6,000 meters off the Irish coast, following the route of Norse and AEConnect-1 cables, which link Europe to the United States. Russia, which had cut the Ukrainian cables in 2014, would therefore have the capacity to repeat the operation for the whole Europe.

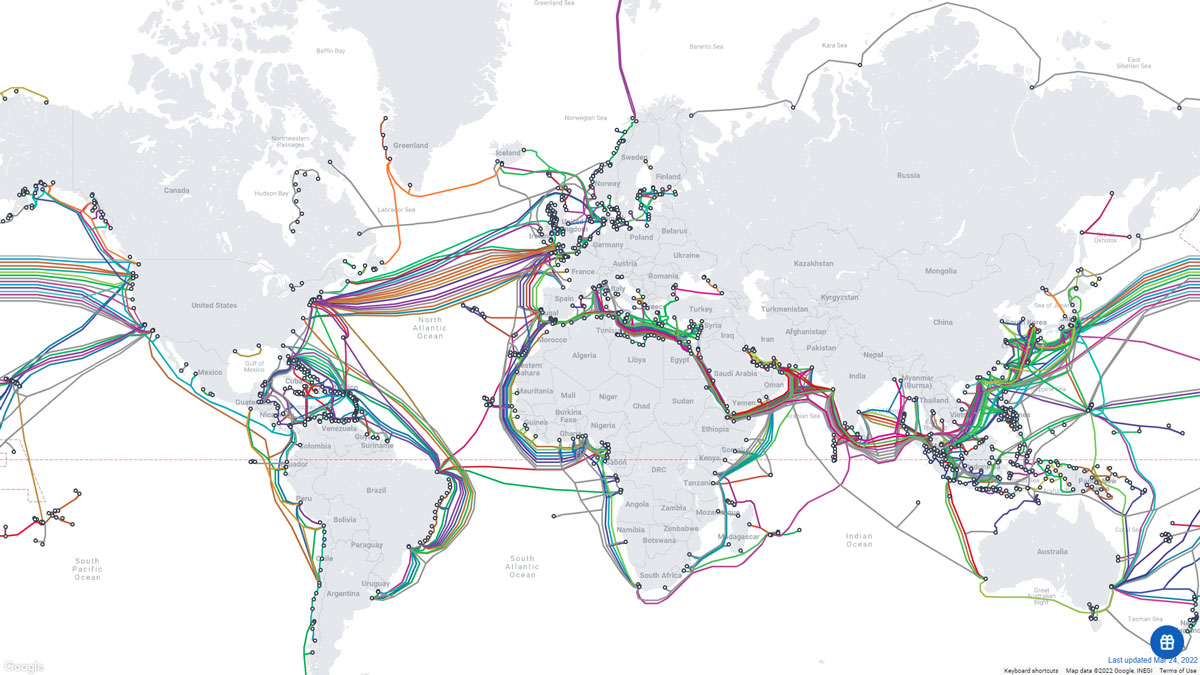

A map of submarine cables around the world

TeleGeography, a US telecommunications consultancy, has created the Submarine Cable Map portal, an interactive map of all submarine cables unfolding around the world, with data about the companies that own them, such as Google, Facebook, Amazon, Verizon, or AT&T. On the map, we can see that a key highway is in the Atlantic Ocean, which links Europe and North America. In the meantime, the Great Pacific Highway links the United States of America to Japan, China, and other Asian countries. From Miami, several cables connect Central and South America. In the case of Mexico, for example, most cables run from the east of the country, cross the Gulf of Mexico to Florida and from there they connect to Central and South America.

Even if we have the tendency to believe that our smartphones, computers, and other cars are interconnected by space, most – almost 99% of all internet traffic – is thus carried by global telecommunications sublines. There are over 420 cables in the world, totalling 1.3 million kilometres, over three times the distance from Earth to Moon. Record: 39,000 kilometres length for the SEA-ME-WE 3 cable, which links South-East Asia to Western Europe through the Red Sea.

Cutting submarine cables, an old and proven practice of war

Recent attacks on cables carrying voice and data traffic between North America and Europe lead to the idea that they seem to be undergoing a new development. France and the United Kingdom had already dealt with this experience on the part of the Germans during the First World War. These infrastructures were part of the global cable telegraph network. Similarly, the United States cut wartime cables as a means of disrupting the ability of an enemy power to command and control distant forces.

The first such attacks took place in 1898, during the Spanish-American War. That year, in the Gulf of Manila (Philippines), the USS Zafiro cut the cable connecting Manila to the Asian continent to isolate the Philippines from the rest of the world, as well as the cable connecting Manila to the Philippine city of Capiz. Other spectacular cable attacks took place in the Caribbean, plunging Spain into the dark during the conflict in Puerto Rico and Cuba, which contributed greatly to the final victory of the United States.

Russia interested in NATO’s subsea infrastructure

Russia seems to materialize the concerns at the highest level in this field. In 2015, the presence of Russian vessel Yantar along the US coast, near the cables, did not fail to arouse tensions between the two states. At the end of 2017, the situation repeated.

“We are now seeing Russian underwater activity in the vicinity of undersea cables that I don’t believe we have ever seen. Russia is clearly taking an interest in NATO and NATO nations’ undersea infrastructure,” said Admiral Andrew Lennon, commander of the organization’s submarine forces. It’s like going back to the days of the Cold War… To the point where Policy Exchange has devoted an entire chapter of its “Russia Risk” report to this topic. The think tank recalls the episode of the annexation of Crimea in 2014, when the peninsula was isolated from the rest of Ukraine by physically cutting off communications.

“If the relative weakness of the Russian position makes a conventional conflict with NATO unlikely, fibre-optic cables can be a target for Russia. We should prepare for an increase in hybrid actions in the maritime field, not only in Russia, but also in China and Iran,” underlines the former commander of the NATO allied forces, the American Admiral James G. Stravridis.

Three major security risks

The first risk factor is the growing volume of data flowing through cables, which encourages third countries to spy on or disrupt traffic.

The second risk factor is the increasing capital intensity of these facilities, which leads to the creation of international consortia involving up to dozens of owners. These owners are separated from the entities that produce the cable components and from those that position the cables along the ocean floor. Timeshare makes it possible to reduce costs substantially, but at the same time allows the entry in these consortia of state actors who could use their influence to disrupt data flows, or even to interrupt them in a conflict scenario. At the other end of the spectrum, GAFAMs (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft) now have the financial and technical capacity to build their own cables. Thus, the Dunant cable, which links France to the United States, is entirely owned by Google. The Chinese giants have also embarked on a strategy of submarine conquest: this is the case of the Peace cable, which connects China to Marseilles, owned by the Hengtong company, considered by the Chinese government as a model of “civilian-military”.

Another threat is espionage, which requires specially equipped submarines, or submarines operating from ships, capable of intercepting, or even modifying, data passing through fibre-optic cables without damaging them. So far, only China, Russia and the United States have such means.

The most vulnerable point of submarine cables, however, is where they reach land: the landing stations Thus, the town of Lège-Cap-Ferret, where the interface room between the Franco-American cable “Amitié” will be built, has recently become a veritable nest of spies, according to informed sources.

But the most worrying trend is that more and more cable operators are using remote management systems for their networks. Cable owners are excited about the staff cost savings. However, these systems have poor security, which exposes submarine cables to cyber security risks.

Solutions in case of multiple attacks

The US executive has recently investigated possible risks in the event of multiple attacks. In addition to expanding the SSGP grant program, it has encouraged the Maritime Administration to involve various civil society associations, such as the International Propeller Club, in programs designed to minimize these threats. The idea is to create a kind of “submarine cable militia” capable of responding quickly in a crisis.

The Propeller Club has more than 6,000 members and has recently provided $ 3.5 billion in aid to the maritime industry in the fight against Covid-19. Similarly, the creation of a “submarine cable Airbus” capable of competing with GAFAMs, whose market share could increase from 5% to 90% in six years, can obviously become a reality only if Europe pays attention to this topic.

In a context of growing international tensions, the creation of a European program modelled on the US and Japanese programs, which aims to increase operations to deter attacks on these infrastructures and to develop a high-stakes construction and repair, has become very important.