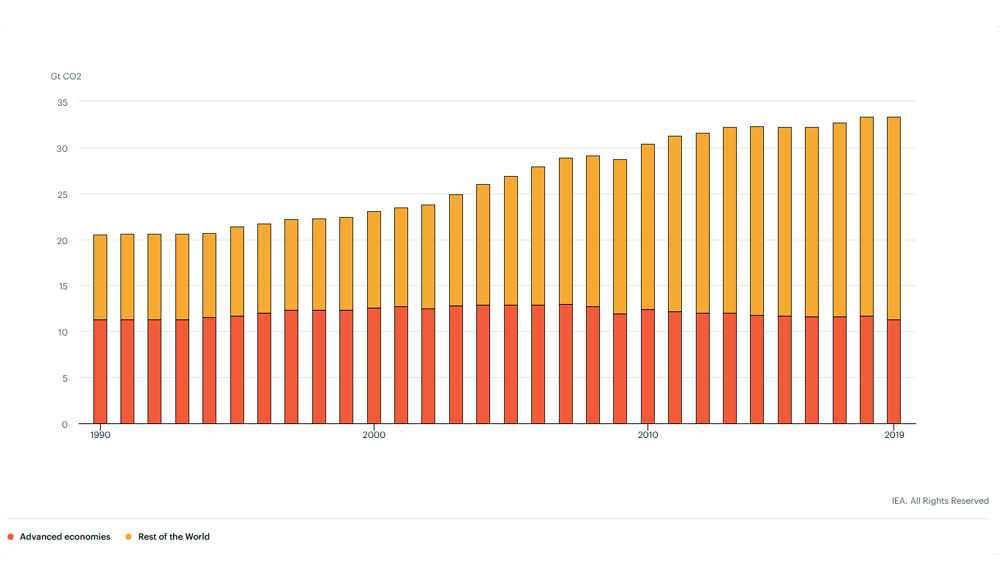

Global Carbon Dioxide Emissions Flatlined in 2019

Despite widespread expectations of another increase, global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions stopped growing in 2019, according to IEA data released on February 11.

After two years of growth, global emissions were unchanged at 33 gigatonnes in 2019 even as the world economy expanded by 2.9%. This was primarily due to declining emissions from electricity generation in advanced economies, thanks to the expanding role of renewable sources (mainly wind and solar), fuel switching from coal to natural gas, and higher nuclear power generation. Other factors included milder weather in several countries, and slower economic growth in some emerging markets.

“We now need to work hard to make sure that 2019 is remembered as a definitive peak in global emissions, not just another pause in growth,” said Dr Fatih Birol, the IEA’s Executive Director. “We have the energy technologies to do this, and we have to make use of them all. The IEA is building a grand coalition focused on reducing emissions – encompassing governments, companies, investors and everyone with a genuine commitment to tackling our climate challenge.”

A significant decrease in emissions in advanced economies in 2019 offset continued growth elsewhere. The United States recorded the largest emissions decline on a country basis, with a fall of 140 million tonnes, or 2.9%. US emissions are now down by almost 1 gigatonne from their peak in 2000. Emissions in the European Union fell by 160 million tonnes, or 5%, in 2019 driven by reductions in the power sector. Natural gas produced more electricity than coal for the first time ever, meanwhile wind-powered electricity nearly caught up with coal-fired electricity. Japan’s emissions fell by 45 million tonnes, or around 4%, the fastest pace of decline since 2009, as output from recently restarted nuclear reactors increased. Emissions in the rest of the world grew by close to 400 million tonnes in 2019, with almost 80% of the increase coming from countries in Asia where coal-fired power generation continued to rise.

Across advanced economies, emissions from the power sector declined to levels last seen in the late 1980s, when electricity demand was one-third lower than today. Coal-fired power generation in advanced economies declined by nearly 15% as a result of growth in renewables, coal-to-gas switching, a rise in nuclear power and weaker electricity demand.

“This welcome halt in emissions growth is grounds for optimism that we can tackle the climate challenge this decade,” said Dr Birol. “It is evidence that clean energy transitions are underway – and it’s also a signal that we have the opportunity to meaningfully move the needle on emissions through more ambitious policies and investments.”

To support these objectives, the IEA will publish a World Energy Outlook Special Report in June that will map out how to cut global energy-related carbon emissions by one-third by 2030 and put the world on track for longer-term climate goals.

The Agency will also hold an IEA Clean Energy Transitions Summit in Paris on 9 July, bringing together key government ministers, CEOs, investors and other major stakeholders from around the world with the aim of accelerating the pace of change through ambitious and real-world solutions.

Dr Birol will discuss these results and initiatives tomorrow at a special IEA Speaker Series event at IEA Headquarters in Paris with energy and climate ministers from Poland, which hosted COP24 in Katowice; Spain, which hosted COP25 in Madrid; and the United Kingdom, which will host COP26 in Glasgow this year.

The United States saw the largest decline in energy-related carbon dioxide emissions in 2019 on a country basis – a fall of 140 Mt, or 2.9%, to 4.8 Gt. US emissions are now down almost 1 Gt from their peak in the year 2000, the largest absolute decline by any country over that period. A 15% reduction in the use of coal for power generation underpinned the decline in overall US emissions in 2019. Coal-fired power plants faced even stronger competition from natural gas-fired generation, with benchmark gas prices an average of 45% lower than 2018 levels. As a result, gas increased its share in electricity generation to a record high of 37%. Overall electricity demand declined because demand for air-conditioning and heating was lower as a result of milder summer and winter weather.

Energy-related CO2 emissions in the European Union, including the United Kingdom, dropped by 160 Mt, or 5%, to reach 2.9 Gt. The power sector drove the trend, with a decline of 120 Mt of carbon dioxide emissions, or 12%, resulting from increasing renewables and switching from coal to gas. Output from the European Union’s coal-fired power plants dropped by more than 25% in 2019, while gas-fired generation increased by close to 15% to overtake coal for the first time.

Germany spearheaded the decline in emissions in the European Union. Its emissions fell by 8% to 620 Mt of carbon dioxide emissions, a level not seen since the 1950s, when the German economy was around 10 times smaller. The country’s coal-fired power fleet saw a drop in output of more than 25% year on year as electricity demand declined and generation from renewables, especially wind (+11%), increased. With a share of over 40%, renewables for the very first time generated more electricity in 2019 than Germany’s coal-fired power stations.

The United Kingdom continued its strong progress with decarbonisation as output from coal-fired power plants fell to only 2% of total electricity generation. Rapid expansion of output from offshore wind, as additional projects came online in the North Sea, was a driving factor behind this decline. Renewables provided about 40% of electricity supply in the United Kingdom, with gas supplying a similar amount. The share of renewables became even higher in the later part of the year, with wind, solar PV and other sources generating more electricity than all fossil fuels combined during the third quarter.

Japan saw energy-related carbon dioxide emissions fall 4.3% to 1 030 Mt in 2019, the fastest pace of decline since 2009. The power sector experienced the largest drop in emissions as reactors that had recently returned to operation contributed to a 40% increase in nuclear power output. This allowed Japan to reduce electricity generation from coal-, gas- and oil-fired power plants.

Emissions outside advanced economies grew by close to 400 Mt in 2019, with almost 80% of the increase coming from Asia. In this region, coal demand continued to expand, accounting for over 50% of energy use, and is responsible for around 10 Gt of emissions. In China, emissions rose but were tempered by slower economic growth and higher output from low-carbon sources of electricity. Renewables continued to expand in China, and 2019 was also the first full year of operation for seven large-scale nuclear reactors in the country.

Emissions growth in India was moderate in 2019, with carbon dioxide emissions from the power sector declining slightly as electricity demand was broadly stable and strong renewables growth prompted coal-fired electricity generation to fall for the first time since 1973. Continued growth in fossil-fuel demand in other sectors of the Indian economy, notably transport, offset the decline in the power sector. Emissions grew strongly in Southeast Asia, lifted by robust coal demand.