Metals for Clean Energy

From a Hydrocarbon-intensive World to a Metal-intensive World

A new report published by KU Leuven – Metals for Clean Energy: Pathways to solving Europe’s raw materials challenge, shows that metals will play a central role in successfully building Europe’s clean technology value chains and meeting the EU’s 2050 climate-neutrality goal. In the wake of supply disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Europe’s lack of resilience for its growing metals needs has become a strategic concern.

The study evaluates how Europe can fulfil its goal of “achieving resource security” and “reducing strategic dependencies” for its energy transition metals, through a demand, supply, and sustainability assessment of the EU Green Deal and its resource needs.

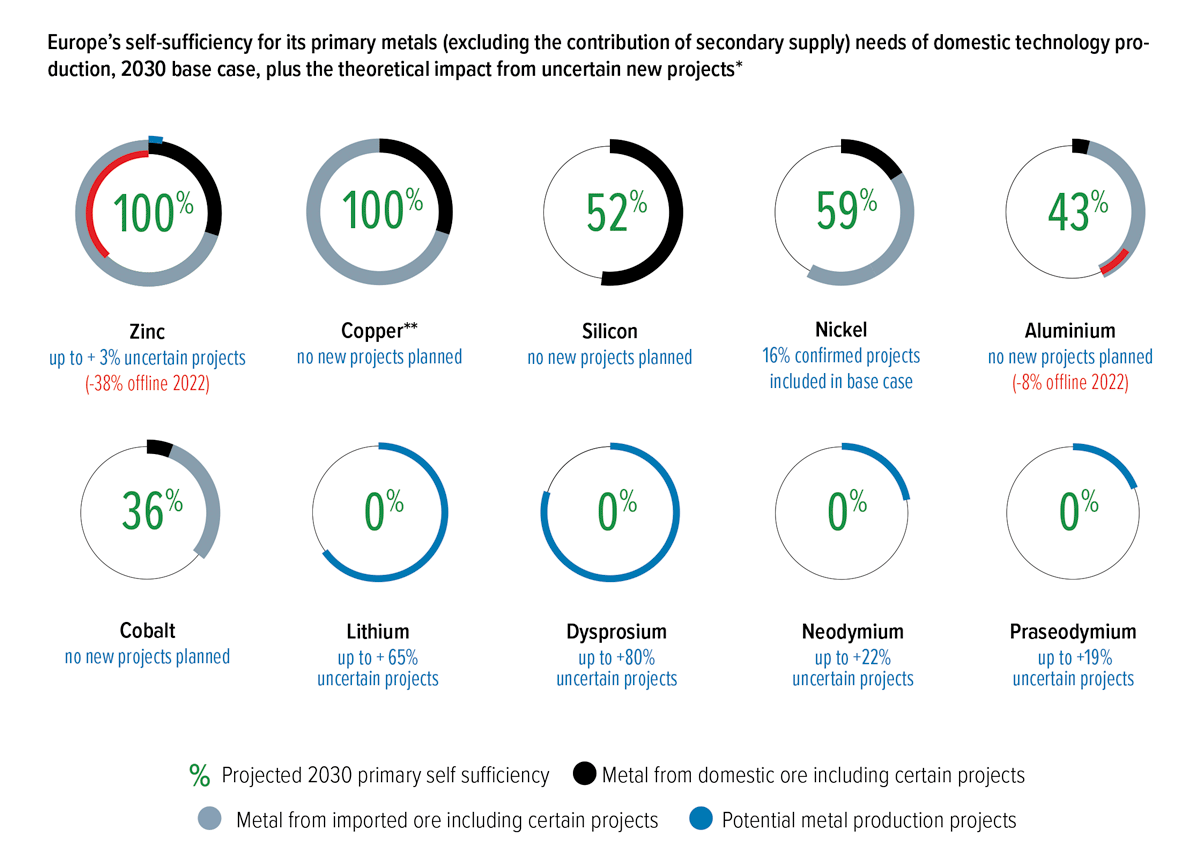

It concludes that Europe has a window of opportunity to lay the foundation for a higher level of strategic autonomy and sustainability for its strategic metals through optimized recycling, domestic value chain investment, and more active global sourcing. But firm action is needed soon to avoid bottlenecks for several materials that risk being in global short supply at the end of this decade.

Dependence on strategic metals

Mining industry experts recall that Europe needs strategic metals essential for energy transition. Europe, whose mining activity in the field of strategic metals is extremely low in relation to its economic share, does not integrate fast enough the rapid and brutal transformation of the world and its rules of the game. In absence of a strong and rapid reaction, economic strategy could be undermined by the lack of sovereignty over the new strategic raw materials (essentially metals such as cobalt, nickel, neodymium, rhenium, etc.), to the point of facing shortage, becoming dependent on foreign powers, or not having another alternative than the import of finished products.

The doctrine established for decades in terms of strategic procurement is the one that maximizes financial indicators. The concepts of ‘invisible hand’ of the market, zero actions, Just-in-Time (JIT), futures contracts emerged as a goal in a world where globalization and liberalism were synonymous with progress. This is still a widespread opinion. Can Europe still rely on this theory for its development and sovereignty? Mankind must achieve within 30 years a titanic project, unprecedented in the history of Humanity, the energy transition.

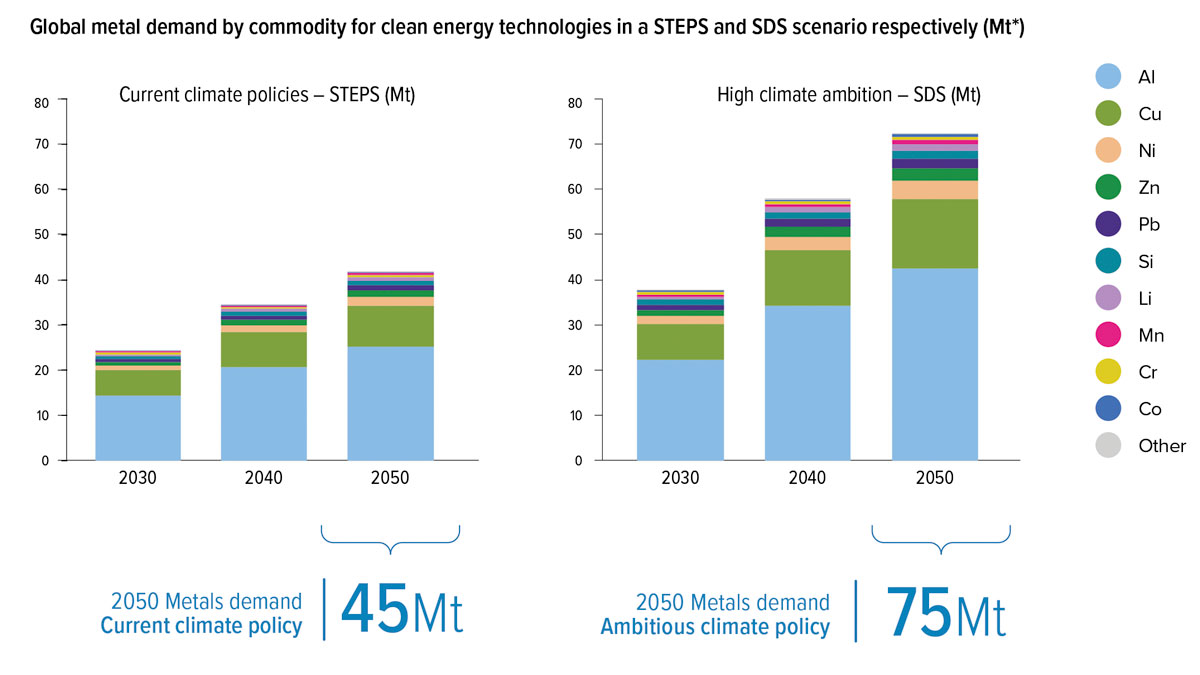

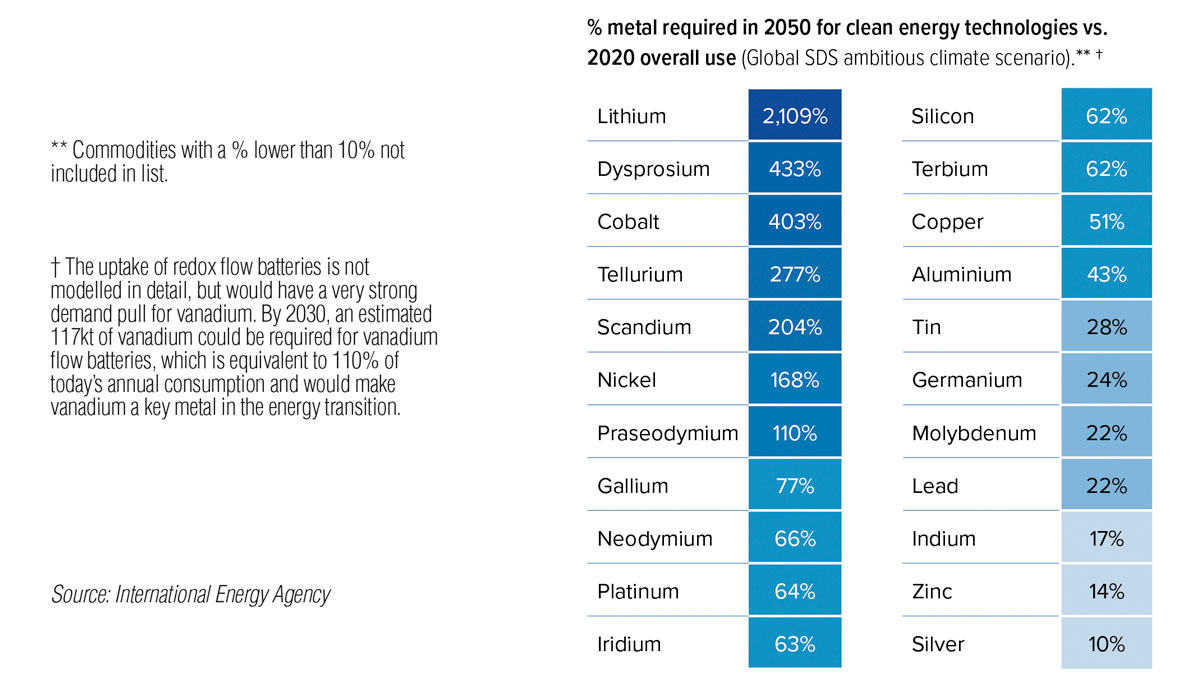

But new energies are intermittent and diluted in space: it is necessary to store and mobilize more materials to produce and distribute the same amount of energy. Therefore, we move from a hydrocarbon-intensive world to a metal-intensive world. Scientific work that quantifies the implications of this transition – like those of the director of research at the Institute of Earth Sciences in Grenoble, Olivier Vidal – arouse the interest of experts. “By 2050 alone, we will have to extract as many metals as we have done since the dawn of Humanity”, says Olivier Vidal. And no model is sustainable until the end of the century without a recycling rate that has never been reached before.

Ordered in September 2021 by the Ministries of Ecological Transition and Industry of France, the Varin report on ensuring the supply of mineral raw materials shed light on the problem of the supply of mineral raw materials on a continental scale.

In a context of strong tensions over the mineral raw materials, exacerbated by the new needs in the field of decarbonization of electric mobility or renewable energy sectors, the French Government entrusted to Philippe Varin, former President of France Industrie, the mission of ensuring the supply of the industry. Especially the evaluation, together with manufacturers, of the security of supply of the specific metals required.

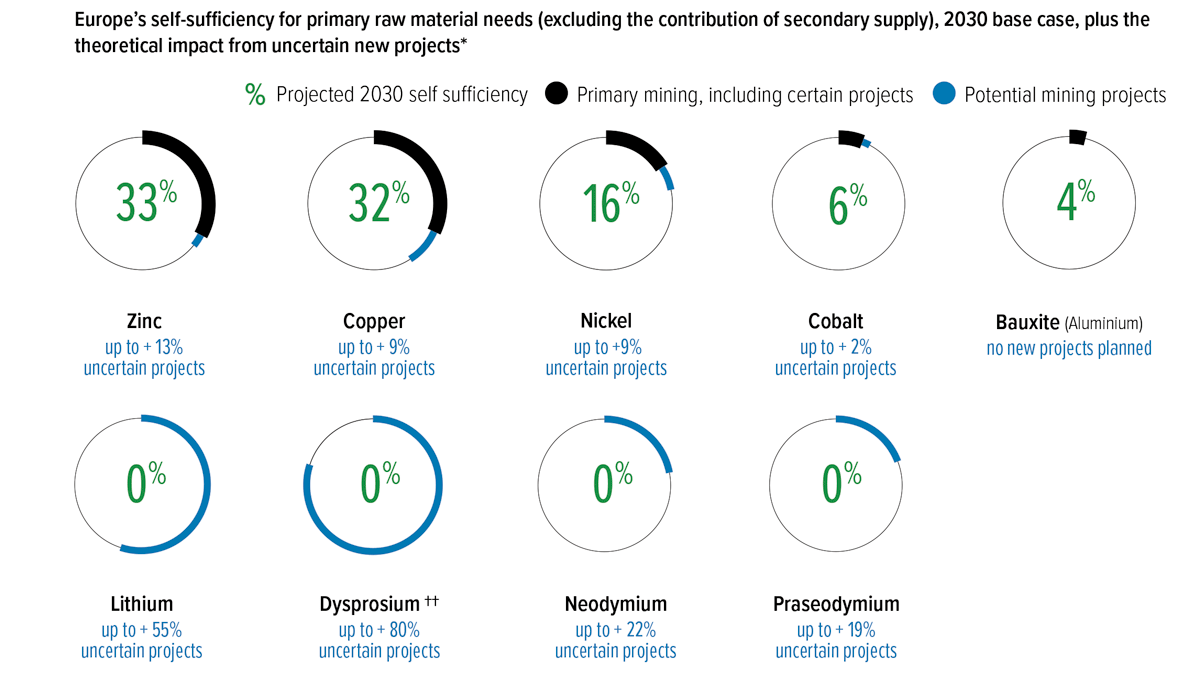

Unsurprisingly, according to Philippe Varin, the European Union has fallen behind China, which has 20 years ahead in the strategic metals supply chain. EU’s dependence is worrying. He added that even by 2030, in Europe only 20 to 30% of needs could be covered by European suppliers. The risk of shortages seems very real, especially when it is correlated with the European objectives. The ecological and digital transition cannot do without these metals, for example to produce electric batteries.

In September 2020, the European Commission had already addressed the issue, preparing a document with the situation in EU countries.

The supporting tables showed, element by element, the EU’s dependence on the import of critical raw materials (including those mentioned above). Raw materials that are not produced or hardly produced in EU countries are nevertheless used to manufacture products used by EU consumers and are imported from China (silicon, lithium, rare earths), but also Chile (lithium), Democratic Republic of Congo (cobalt) and many other large producers export these raw materials to EU countries.

How does France ensure the supply of strategic metals

The French Government has decided to follow three major recommendations of the Varin report:

- Creating a public/private investment fund in strategic metals to ensure the supply of battery factories.

- The development of two ‘industrial platforms’ to bring together in Dunkerque the players in the sectors of electric batteries and permanent magnets, refining, manufacture of ternary preliminary products (precursors), training, as well as from the recycling sector at Lacq (a locality known for oil and gas exploitation).

- Finally, the state is based on the synergy between manufacturers and researchers to innovate – the Bureau of Geological and Mining Research (BRGM) of the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) or CEA (the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission).

Five strategic axes selected

At the end of this paper, focused primarily on battery metals (nickel, cobalt, lithium) and permanent magnets (rare earths), which are particularly critical for electromobility and new energies, the French Government adopted the following strategic axes:

- Launching the preparatory works to create an investment fund in strategic metals necessary for energy transition. The goal is to contribute to ensuring the supply of French and European manufacturers, by capital investment and establishing long-term supply contracts.

- Creating an observatory of critical metals.

- Appointment of an inter-ministerial delegate for securing the supply of strategic metals in close cooperation with the industry.

- Development, within the battery-dedicated acceleration strategy, of technological roadmaps shared between manufacturers and public research on the metals of the next generation of batteries.

- Translation of the concept of ‘responsible mining’ into a certifiable standard or label.

Today, France imports 100% of the needs, as it wants to avoid any shortage of metals – as it happened to electronic components in 2021 – to supply the electric batteries planned to produce the equivalent of 600 to 800 GWh across Europe.

To strengthen the metal supply chains, the French government announced the opening of a first call for projects, which aims at critical metals intended for the strategic industrial sectors. It will support the best investment projects, by supporting the initiatives that can be quickly industrialized in the region. The selection of the emerging players will have priority within this call.

Investment projects can take the following shapes:

- Creation of new production units

- Investments in the existing production units to significantly transform their processes or production capacities, while making them more productive and more flexible

- Development and implementation at industrial scale the innovative technological processes that save raw materials and energy

The ‘Critical Metals’ call for projects is open until 30 January 2024.

EU awareness to ensure its supply

European funding for research and development and internal innovation are important areas for contribution to the development of the capabilities of European industries. In the end, the development of internal supply and choosing to diversify this supply in third countries must also contribute to the reduction of EU’s dependence.

Some projects have already started, for example in the automotive industry. At the end of 2021, the Swedish electric batteries group Northvolt announced the launch of production at its new factory located in Sweden.

Giants such as BMW or Volkswagen and Volkswagen have already placed orders on the site.

Northvolt is expecting to equip in the end one million electric vehicles per year due to the 3,000 employees on the site. It is the first signal of this type in Europe, and it is expected to also motivate others. Therefore, around twenty ‘mega-factories’ are planned in Europe that are based on the potential of resources present on EU territory.

The challenge is to ensure the supply, especially for manufacturers of batteries (nickel, cobalt, lithium) for electric cars or even permanent magnets (which require certain rare earths) for offshore wind turbines in the context of an economy whose new paradigm is decarbonization.

There is an urgent need as the health crisis has shown the fragility of supply chains. Control of the entire value chain is needed to reduce EU’s dependence, especially on China, which, according to Philippe Varin, is 20 years ahead of Europe.

Renewable energy long behind hydrocarbons in Europe

Renewable energy has recently dethroned nuclear energy and coal among Europe’s energy sources. But it provides only a sixth of what is consumed, far behind oil and gas, whose recent price increases are fuelling inflation.

Europe is in a situation of double dependence, both on sun and wind, which are not always sufficient, as well as on suppliers outside the EU for hydrocarbon supply.

Shale oil or gas production in the European Union is insignificant, equivalent to 3% of the total fuel consumed, reaching a historic low last year. In total, the European Union produces only 39% of energy, mainly renewable and nuclear. The rest, i.e., 61%, comes at a rate of two thirds from oil (a quarter from Russia, ahead of Iraq, Nigeria, and Saudi Arabia), a quarter from gas (Russia, up to 30% of the purchases, then Norway, Algeria, and Qatar), in addition to relatively small quantities of coal.

This dependence varies greatly between European countries. Due to nuclear energy, gas accounts for only a sixth of energy consumed in France, of which 15% comes from Russia, behind Norway. Instead, Moscow ensures half of Germany’s gas imports, which heat half of the country’s homes.

Conclusion

More than ever, a European strategy is necessary for the supply of raw materials. If it is necessary to develop the recycling of these raw materials, this activity will not be able to meet all the needs of EU countries. The European and national laws will then have to actively promote the mining and processing of these raw materials in EU countries. Many economic sectors are affected by this industrial problem. Probably the most visible of all is the electric car sector.

The stakes are numerous, especially from the desire to reduce European dependence on producing countries. By improving the availability of these raw materials in a close geographical area, the objective is also to avoid shortage in the supply chain.