A long-term view of natural gas security in the European Union

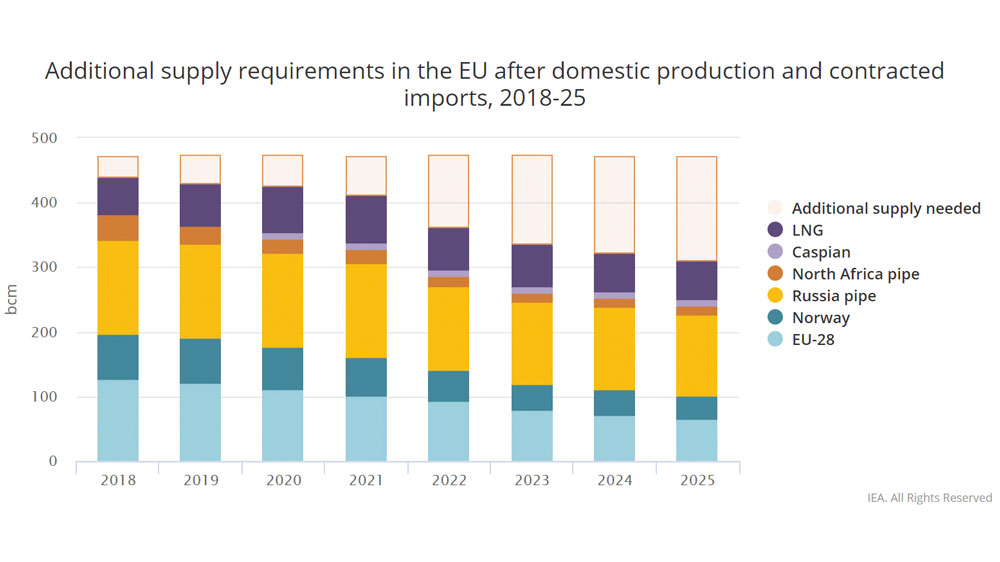

The security of European natural gas supplies has rarely been far off the political agenda. New gas pipeline and LNG projects command high levels of attention, particularly in the context of the European Union’s growing need for imports: its own production is declining; around 100 billion cubic metres (bcm) of long-term contracts expire by 2025; and there is some upside for gas consumption – at least in the near term – as coal and nuclear plants are retired. We estimate that the EU will have to seek additional imports by 2025 to cover up to one-third of its anticipated consumption.

At the moment, Russia is sending record volumes to Europe while LNG utilisation rates remain relatively low. Limits to European production capacity and import infrastructure (with over half of pipelines operating at monthly peaks above 80%) may contribute to market tightness over the coming years, particularly if Asia continues to absorb the ramp up in global LNG liquefaction capacity.

Over the long-term, our projections in the latest World Energy Outlook suggest that Russia is well placed to remain the primary source of gas into Europe. LNG imports are projected to grow, as new suppliers – notably the United States – increase their presence on international markets and more European countries build LNG regasification capacity. However, Russia is still projected to account for around one-third of the EU’s supply requirements through to 2040.

But import dependence is only one part of the gas security equation. Less attention is being paid to three issues that may, in the long run, have an even greater impact on gas security in the European Union: how easily gas can flow within the European Union itself; how patterns of demand might change in the future; and what role gas infrastructure might play in a decarbonising European energy system.

A liberalised internal gas market

Whether or not gas can flow easily across borders within the European Union is a key focus of the EU’s Energy Union Strategy. On this score, our analysis suggests that the internal market is already functioning reasonably well: around 75% of gas in the European Union is consumed within a competitive liquid market, one in which gas can be flexibly redirected across borders to areas experiencing spikes in demand or shortages in supply. Bidirectional capacity has been instrumental in this regard.

That said, there are a few areas where markets and physical interconnections need further development. For example, roughly 80 billion cubic metres (bcm), or 40%, of the EU’s LNG regasification capacity cannot be accessed by neighbouring states, and some countries in central and southeast Europe still have limited access to alternative sources of supply.

On the whole, our projections suggest that targeted implementation of the European Union’s Projects of Common Interest (PCI) and full transposition of internal gas market directives can remove remaining bottlenecks to the completion of a fully-integrated internal gas market, thereby enhancing the security and diversity of gas supply. With LNG import capacity and pipeline projects like the Southern Gas Corridor increasing Europe’s supply options, the gas market in an ‘Energy Union’ case can build up its resilience to supply shocks while enabling short-term price signals, rather than fixed delivery commitments, to determine optimal imports and intra-EU gas flows.

However, this cannot be taken for granted. If spending on cross-border gas infrastructure were frozen and remaining contractual and regulatory congestion persists, then peak capacity utilisation rates would rise alongside the growth of European gas imports: around half of the EU’s import pipelines would run at maximum capacity in 2040 in this Counterfactual case, compared with less than a quarter in an Energy Union case.

Whether higher utilisation of the EU’s gas ‘hardware’ poses a security risk depends in large part on the strength of the ‘software’ of the internal market. The marketing of futures, swap deals and virtual reverse flows on hubs can remove the physical element of gas trading, while also allowing volumes to be bought and sold several times before being delivered to end-users. Along with more transparent rules for third party access to cross-border capacity, this might preclude some of the need for additional physical gas infrastructure and, in time, enable gas deliveries to be de-linked from specific suppliers or routes. Infrastructure investment decisions therefore require careful cost-benefit analysis, particularly as the debate about the pace of decarbonisation in Europe intensifies.

Security and demand

A second issue for long-term European gas security is the composition of demand. Winter gas consumption in the European Union (October-March) is almost double that of summer (April-September). The majority of this additional demand is required for heating buildings; this seasonal call is the primary determinant of gas infrastructure size and utilisation.

In the IEA’s New Policies Scenario, ambitious efficiency targets are projected to translate into a retrofit rate of 2% of the EU’s building stock each year, starting in 2021. Together with some electrification of heat demand, this would lead to a 25% drop in projected peak monthly gas demand in buildings by 2040.

This reduction in demand from the buildings sector more than offsets a 50% increase in peak gas demand for power generation, which is needed to support increasing amounts of electricity generated from variable sources, notably wind. Along with gradual declines in industrial demand, the net effect by 2040 is a reduction in monthly peak demand for gas by almost a third.

Such a trajectory for gas demand has significant commercial implications; reduced gas consumptions in buildings would lead to an import bill saving of almost EUR 180 billion for the EU as a whole over the period 2017-2040. However, it also poses challenges for mid-stream players – e.g. grid and storage operators as well as for utilities:

- For grid operators, structural declines in gas demand for heating means that the need for additional infrastructure is more uncertain, and what already exists may see falling utilisation (as discussed in WEO 2017). Capacity-based charges to end users typically contribute the most to cost recovery, and underpin the maintenance of the system. But, over time, higher operating costs for ageing infrastructure might need to be recovered from a diminishing customer base at the distribution level. This may further reinforce customer fuel switching over the long term.

- For storage operators, the slow erosion of peak demand for heating implies an even more pronounced flattening of the spread between summer and winter gas prices, further challenging the economics of seasonal gas storage.

- For utilities, with the anticipated declines in nuclear and the phasing out of coal-fired power plants in Europe, alongside the growth of variable renewable electricity, gas-fired power plants need to ramp up and down in short intervals in order to maintain power system stability. This flexible operation means a reduction in running hours but a continued need to pay for a similar amount of fuel delivery capacity (whether or not the gas itself comes from import pipelines or short-term storage sites).

A new set of questions for Europe’s gas infrastructure

The debate on Europe’s gas security has tended to concentrate on external aspects, mainly the sources and diversity of supply. But the focus may be shifting to internal questions over the role of gas infrastructure in a decarbonising European energy system, and the system value of gas delivery capacity.

A key dilemma is that, while Europe’s gas infrastructure might be needed less in aggregate, when it is needed during the winter months there is – for the moment – no obvious, cost-effective alternative to ensure that homes are kept warm and lights kept on. The amount of energy that gas delivers to the European energy system in winter is around double the current consumption of electricity. Moreover, the importance of this function and the difficulty of maintaining it both increase as Europe proceeds with decarbonisation. As the European Union contemplates pathways to reach carbon neutrality in the Commission’s latest 2050 strategy, options to decarbonise the gas supply itself are gaining traction – notably with biomethane and hydrogen (we will be exploring these options in WEO 2019).

In order to stay relevant, natural gas infrastructure must evolve to fulfil additional functions beyond its traditional role of transporting fossil gas from the wellhead to the burner tip. Traditional concerns around security of supply of course remain relevant, but there are more things to value than volume. The security of the future gas system will increasingly depend on its versatility, flexibility, and the pricing of ‘externalities’ such as carbon emissions, air pollution or land use. Europe’s gas infrastructure is an undoubted asset. But, like many other pieces of energy infrastructure, it will need to adapt to the demands of sustainable development.

Text by Peter Zeniewski, WEO Energy Analyst