Research and innovation in Romania, a land of two realities

At European Union (EU) level, Romania is a junior in innovation. Insufficient funding aside, a more damaging factor are the self-created domestic obstacles, by which legitimate research is over-shadowed and/or squeezed out by weak projects draining a significant part of the national funds. Given the inefficiencies of national funding mechanisms, the main driver of innovation (in all sectors) are the European policies and funds. There are a few high-prestige R&D projects (such as the ELI-NP – Romania’s star public research project) in what otherwise could be described as a sea of yet-to-be-fulfilled potential. There could be so many more-high value-added projects, if only Romania cleaned up house and enforced strict integrity and accountability rules in its academic and research establishment. That means not only pressing ahead with serious research, but calling out the impostors and a zero-tolerance towards plagiarism.

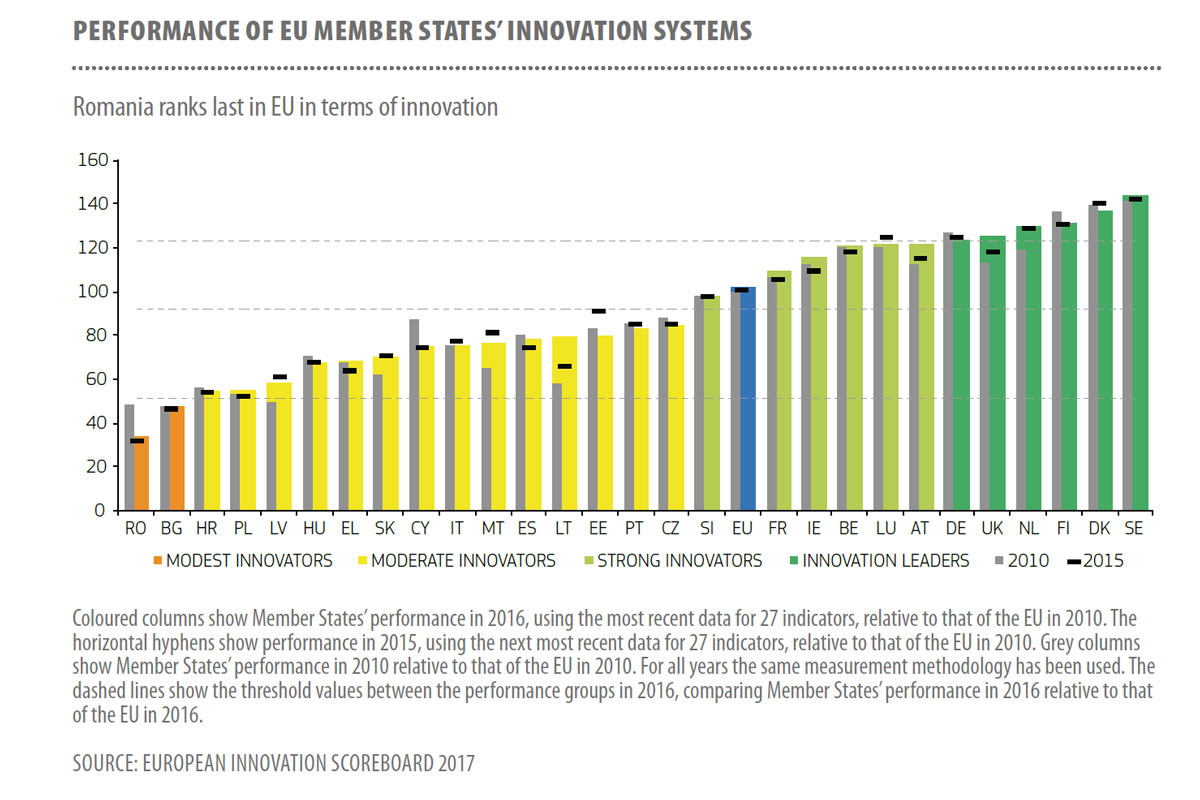

There is a growing gap between how Romania perceives itself and how it actually ranks in research and innovation compared to other European countries. On the one hand, Romania is home to new cutting-edge research infrastructure projects such as the Extreme Light Infrastructure – Nuclear Physics (ELI-NP) – a pan-European research project hosted by 3 countries (Czech Republic, Hungary and Romania). The three pillars of the project are: ELI – Beamlines (Prague), ELI – Attoseconds (Szeged), and ELI-NP (Bucharest). The Romanian leg of the ESFRI project is developed in Magurele and overseen by the National Institute of Physics and Nuclear Engineering Horia Hulubei (IFIN-HH). Scheduled to become operational in early 2019, ELI-NP is the largest investment so far in Romania’s R&D system and will result in an interdisciplinary research facility described as the most advanced European and global one dedicated to the study of photonuclear physics and its applications (in nuclear materials, radioactive waste management, material science and life sciences). The project is financed from EU structural funds in 2 cycles: in phase I (2013-2015) total investment reached EUR 179 million; in phase II (2016-2018) it will be EUR 205 million. However, despite this and other great projects being implemented in Romania, the country ranks last in EU in terms of innovation. On aggregate, Romania’s research, development and innovation (RDI) system is an underperformer, not only at EU level, but also in its regional group of peer CEE countries.

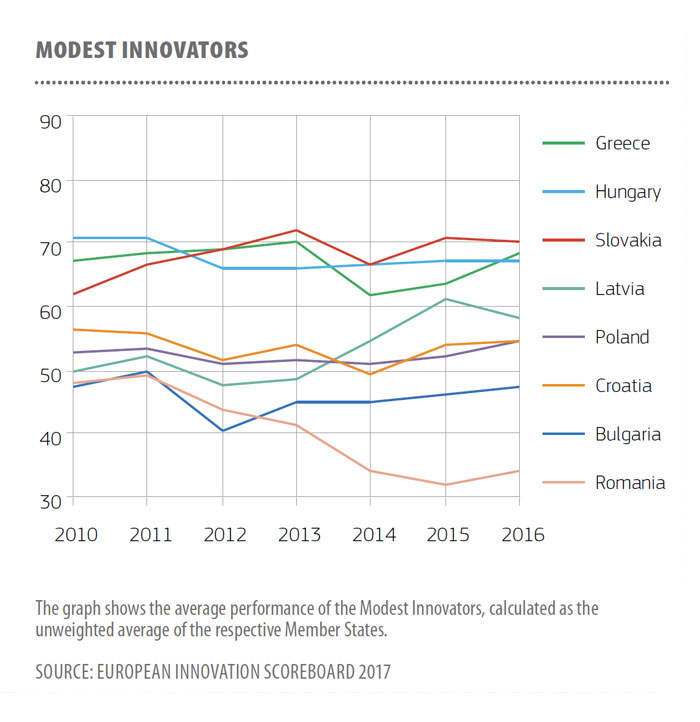

According to the European Innovation Scoreboard, the year 2015 has seen the worst performance in innovation since Romania joined the EU. While accounting for the effects of the economic crisis (2010-2012), Romania’s individual evolution declined abruptly since 2012. Even compared to Bulgaria, Romania’s innovation performance took a nosedive (notice the steep divergence between the two countries starting with mid-2012). So, what are the reasons for the current underperformance and downward trend?

While Romania’s government expenditure on R&D (GERD) as % of GDP is an issue (0.5% in 2015 is very low), there are bigger structural problems at stake. Even if Romania increases public spending on R&D to 1% of GDP by 2020, this measure alone will not fix the ills of Romania’s education and research or improve its overall performance overnight. One reason is that there are several established narratives or national myths that no longer have a correspondent in reality:

Romania’s claim of having a great educational system is not supported by current international rankings. Not one of Romanian Universities (not even the best ones – Babes-Bolyai, Politehnica Bucharest, University of Bucharest, Technical University Iasi, and Politehnica Timisoara – are in the Shanghai Top 500 best universities in the world (RIO Country Report 2016: Romania, JRC Science for Policy Report, 2017, pg. 12). It is true, that there is still a strong tradition in math and engineering inherited from the communist time. However, the achievements of Romanian students and scholars today are not so much the product of a strong and modern education system, but the combined result of individual talent, huge sacrifice and commitment made by loving parents and gifted teachers. It is also indicative that much of this talent does not ultimately stay in Romania.

Issues with inefficient distribution of national funding for research: there are widespread reports regarding the ‘unprofessional assessment’ of applications: evaluators without minimum expertise for the job, the exclusion of foreign experts from the assessment process (as of March 2017, under then Research Minister Serban Valeca, foreign experts have been excluded from the assessment process, making it exclusively a domestic affair), non-transparent panels of evaluators – all of which essentially give free reign to favouritism. It also makes it extremely difficult for young researchers (especially Romanian graduates of Western universities) to have their proposals evaluated in a fair manner.

In fact, the opposite seems to occur, weaker insiders are being favoured over competitive outsiders, which results in a huge waste of talent, and eventually brain drain, the long-term impact of which is yet to be fully grasped. Moreover, there is a credibility question mark that hovers over Romania’s entire higher academic production, especially in fields that are not exact sciences (questionable quality and cases of undetected and unsanctioned plagiarism). There is also a circulation problem. Romania’s research system is described as ‘isolated’ by the World of Research 2015 report with little international collaboration. Few Romanian scientists get their work published in accredited Western journals, 60% have never published with an affiliation outside Romania (Alfred Radauer and Laura Roman, The Romanian Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Background Report, DG for Research and Innovation, November 2016, pg. 29).

The lack of a strong reaction from the Romanian scientific and/or professional community to outrageous appointments to top roles (including in education & research) is another issue. In the past few years, a cabal of impostors (people with no or with very weak qualifications, from bottom of the barrel universities, or with plagiarized PhDs) have successfully occupied high public office in Romania (former PM Victor Ponta, ex-Vice Minister and ex-Interior Minister Gabriel Oprea, ex-PM Mihai Tudose).

One factor that accounts for this deterioration is the deep human resource crisis within Romania’s biggest party (PSD) coupled with the excessive politization of public administration (professionals and experts being consistently side-lined in favour of party yes-men for top decision-making roles). This has led to a severe deterioration in public management of the likes Romanian has not seen before and to the appointment of highly unqualified individuals. The most recent example is the case of Valentin Popa, the newly appointed Minister of Education, an obscure university rector, who has publicly stated that: “Our education is good, very good even in some fields, and excellent in some study programs, and it is a pity to shadow these values of the Romanian education system by talking too much about elements that are not so important, such as plagiarism, especially since nowhere in the text of the law does it say that you must use quotes for a text that you take from someone else”.

In response, the rector of the Bucharest University (the only university that has classes on academic integrity in its curricula), Mr. Mircea Dumitru, has resigned from all positions held in the National Council for University Titles, Diplomas and Certifications (CNATDCU) – a rare gesture in Romania. This incident underlines the extent to which public office in Romania has been compromised, but at the same time shows that there are still some parts of an immune system in place. Academic excellence takes a long time to build, but can be easily tarnished. Those who embrace ethical standards and practices in academia have to distance themselves from holders of such views or from holders of unearned academic titles as a matter of principle and as a matter of urgency.

It is not enough for the professionals out there (in institutes, universities, private companies, innovators and entrepreneurs) to press ahead with their work, they need to stand together against incompetence and defend Romanian excellence in research and education against ethical aggressors. That means forcefully reacting to appointments of people who do not meet minimum professional qualifications and a zero-tolerance policy for plagiarism as well as anyone who treats this topic lightly. Until that happens, Romania will continue to be a land of two realities: peaks and islands of excellence (poster projects acting as feedstock for national pride) in a swamp of mediocrity.