Nord Stream: A Roadmap for Secure and Safe Gas for Europe or a Continental Power Play?

Mapping the Projected Benefits and Involved Actors

The Nord Stream 2 is one of the biggest, most innovative, most needed and most scrutinized projects and it aims to provide the means for safe and secure supply of natural gas to the European Union gas market, from Russia.

The European market, with its 28 (not sure about UK) members, is characterized by its depleting indigenous production capacities and an increasing requirement for gas to support the transition to sustainable energy supplies. Nord Stream 2 will complement two already-existing pipelines through the Baltic Sea, and add 55 Billion Cubic Meters (bcm) of design capacity. It is an approximately 1,200km-long offshore natural gas pipeline aiming at to connecting Europe to the world’s largest reserves in Northern Russia. Russia’s state-owned energy giant Gazprom will own and operate the pipeline through its subsidiary Nord Stream 2. The budget for the construction of the pipeline has been estimated to be close to EUR 9.5bn, with Gazprom being the apex contributor to the investment, and the remaining to be financed by Engie, OMV, Royal Dutch Shell, Uniper, and Wintershall.

The project will serve as an expansion of the existing Nord Stream pipeline and is expected to supply energy to approximately 26 million households a year. Initially scheduled for operations in 2019, the new pipeline is expected to deliver gas to European consumers for at least 50 years and contribute to European energy security. The energy delivered by the pipe will be equal to the amount of energy transported using between 600 and 700 LNG tankers; a huge environmental feat.

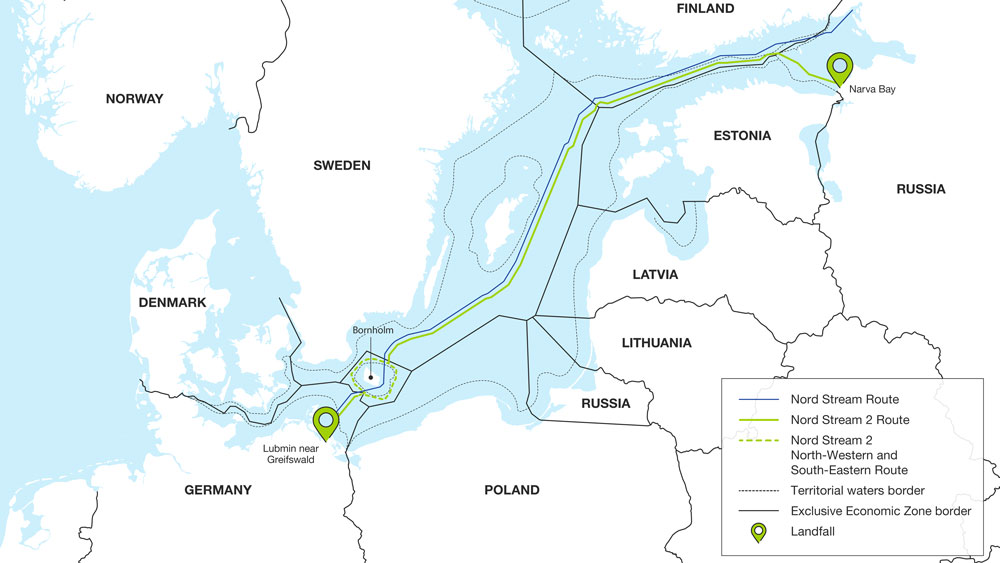

The new pipeline will supply gas from the vast natural gas field of Bovanenkovo in Northern Russia’s Yamal Peninsula, which is estimated to have 4.9 trillion cubic meters (tcm) of gas reserves. This estimate is considered to be more than double compared to the total proven reserves of the EU. The pipeline will make a landing near Greifswald close to the German coast and will have no intermediate compressor station. Nord Stream 2 is planned to follow the route laid down by the Nord Stream pipeline and run through the Baltic Sea from the St. Petersburg region (Russia) to Baltic Coast in north-east Germany.

The route will traverse the territorial waters through the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of five countries including Russia, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany.

History & Context

Discussing about Nord Stream 2, brings us necessarily back to its cradle and its predecessor, Nord Stream (1). The initial Nord Stream twin pipeline system runs through the Baltic Sea from Vyborg, Russia to Lubmin near Greifswald, Germany.

The Nord Stream route crosses the Exclusive Economic Zones of Russia, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Germany, as well as the territorial waters of Russia, Denmark, and Germany.

These two 1,224-kilometre offshore pipelines are the most direct connection between the Russia’s reserves and the energy-hungry European market. Combined, the twin pipelines have a total of capacity of 55 bcm of gas a year to businesses and households in the EU for at least 50 years. The project was considered as a ‘European Success’ and major leverage to the stability and security of the continent.

Construction of Line 1 of the twin pipeline system began in April 2010, and was completed in June 2011. Transportation of gas through Line 1 began in mid-November 2011. Construction of Line 2, which runs parallel to Line 1, began in May 2011 and it was completed in April 2012. Gas transport through the second line began in October 2012. Each line has a transport capacity of roughly 27.5 bcm of natural gas per annum.

In October 2012, the Nord Stream shareholders examined preliminary results of the feasibility study for the third and fourth strings of the gas pipeline and came to the conclusion that their construction was economically and technically feasible. Those new strings (third and fourth in addition to the initial two) came to be known as Nord Stream 2.

In April 2017, Nord Stream 2 AG signed the financing agreements for the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project with ENGIE, OMV, Royal Dutch Shell, Uniper, and Wintershall. These five European energy companies will provide long-term financing for 50 per cent of the total cost of the project. The other half would be financed by Russia’s energy giant, Gazprom.

This came as a natural evolution since European gas demand has been bulging continuously since it recovered on 2014, after its decline following the financial crisis in the early part of the decade. During this period, the European gas market has become increasingly competitive; more than 70% of wholesale gas sales are now based on traded gas market price. Gas demand has grown in all countries and across all sectors.

Moreover, German efforts are already in full development in order to phase-out of coal and lignite, and that could bring Germany’s generation capacity down to 20% of hard coal-and lignite-fired by 2022; eventually lignite and hard coal should be out by 2038. This would occur at the same time as the exit from nuclear power, presenting an additional challenge in closing the power needs gap. It is anticipated that as a result, German gas consumption used for power and heat production could potentially double by 2023.

Major corporations involved and big contracts

The route will traverse the territorial waters through the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of five countries including Russia, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany.

Major corporations from the involved countries will benefit. Kvaerner was awarded a contract worth USD 73m in 2017, for the civil, mechanical and piping works for onshore facilities at the export landfall of the pipeline in Russia.

Europipe, Mülheim, United Metallurgical Company, Chelyabinsk Pipe-Rolling Plant, and Chelyabinsk signed contracts to supply steel pipes for the two pipelines in March 2016. The contract includes the delivery of 2,500km of large-diameter pipes weighing approximately 2.2Mt.

Allseas was awarded a contract by Nord Stream to perform offshore pipe-laying works for the pipeline project in February 2017. The contract also includes the provision of pipe-laying vessels, Solitaire, Pioneering Spirit, and Audacia. Wasco Coatings Germany was contracted in September 2016 to provide concrete weight coating services and pipes for Nord Stream 2 project. In June 2017 Blue Water Shipping was awarded a USD 46m sub-contract by Wasco Coatings for handling, storage, and transportation of the pipeline segments. Bokaalis-Van Oord was awarded the USD 291m rock placement contract for the Nord Stream 2 pipeline project in July 2017. Saipem has been awarded the contract for providing the pipe-laying vessel C10, to be used during the construction of the pipeline.

Other significant actors are: PetrolValves (supplier of critical components), Wasco (weight coating and logistics operations), the HaminaKotka port, Bodac (mitigation measures and munition clearance) and other subcontractors like Metallostroy, MSU-90, and DAF (subcontracted via Russian Dredging & Marine Contractors, as well as through Kvaerner).

Overall, more than a thousand different contractors and subcontractors are engaged in the project, from large international industrial conglomerates, capable of producing thousands of pipes, to one-man firms providing a variety of expert services.

Technical Characteristics

The two twin pipes will stretch over 1,230 kilometres in the Baltic Sea from the Russian to German coast. This route largely runs parallel to the existing Nord Stream system.

The starting point of Nord Stream 2 is located near Narva Bay in the extended Leningrad region, where the pipeline will connect to the Russian gas grid. Gas will be fed into the pipeline from the Slavyansk compressor station, operated by Gazprom. The compressor will calibrate the gas pressure to the level required for secure transportation along the entire pipeline route without the need for intermediate compressor stations. A true mechanical and engineering feat.

Logistics contractors Wasco and Blue Water Shipping work closely with Nord Stream 2 and local suppliers in four Baltic Sea harbours to prepare the pipes and deliver them to the right place, at the right time, at each stage of the project.

The 1,200k pipeline will comprise twin-parallel lines running offshore on the bed of the Baltic Sea. With a total capacity of 55bcm of natural gas a year, the pipeline will be able to cover one-third of the new gas imports required in the next two decades.

The two pipelines of the Nord Stream 2 will have a capacity of 27.5bcm a year each and will comprise 12m-long individual pipe joints. Each pipeline will be made of 100,000 coated steel pipes with 24t in concrete weight. The internal diameter of the pipeline will be 1,153mm (45in) and the wall thickness will be 41mm (1.6in). Orchestrating a massive infrastructure project like the Nord Stream 2 Pipeline requires a precise and efficient logistics plan. Over 200,000 pipe segments must be delivered along the 1,230-kilometre route on an ambitious timeline, and every detail count.

Construction of the Russian section is divided into a 3.7-kilometre-long onshore segment and a 114-kilometre-long offshore segment. It starts 3.8 kilometres away from the shore with the landfall facilities, which include the pipeline inspection gauge (PIG) trap area and shut-down valves, as well as systems to monitor the incoming gas flow and ensure safe operation. Nearshore and offshore construction activities will be performed pipelaying vessels, with these two sections of the pipeline later joined by above-water tie-in.

In the nearshore approaches to the Russian landfall and in the equivalent German part, this includes dredging and backfilling. The pipelines will be buried deep in the seabed to ensure that water and sand movements do not affect stability, which requires the excavation of a deep trench using dredgers. After the pipe has been laid, the trenches will be refilled and the top layer restored with the material previously removed. This accelerates regeneration and ensures that the intervention remains local and limited in time, with the lowest environmental (and not only) impact possible.

Crossing installations will also be needed where the pipeline intersects with telecommunications and power cables, or other gas pipelines. The cable hardware will be protected by thick concrete mattresses. Rock placement is required to ensure pipeline integrity is maintained for its 50-year design lifetime. Rock berms are created to support the pipeline where the seabed is uneven, for example. The same engineering approach has been selected to stabilize the seabed for the pillars of the Rio-Antirio bridge, in Greece.

Because of the… harsh cultural exchanges of the past, the Baltic seabed had to be thoroughly inspected for dumbed munition and ordnance. This required bringing onboard contractors specialized in such operations and that will prevent any impact to construction, operation or valuable cultural heritage. Potential munitions in the route corridor have been cleared using extensive mitigation methods to reduce environmental impacts.

The pipeline will make landfall on the northern German coast near Greifswald. Construction along the 85-kilometre German section of the pipeline is divided into offshore and onshore sections. On the offshore section, the pipeline inspection gauge (PIG) receiving station is being built west of the port of Lubmin. Two 700-metre micro tunnels will make the transition from the onshore to the underwater construction section. These two small tunnels are positioned in front of the PIG receiving station, pass under the infrastructure to the north (railway track, road and supply lines) as well as coastal forest, dune and beach to end in the shallow water area approximately 350 metres beyond the shore.

In the summer of 2018 both pipelines were drawn in via the tunnels to the PIG receiving station. Before this work began, the trench area for both pipelines was prepared in mid-May 2018. In total, a 28-kilometre trench for each pipeline, as well as two parallel 21-kilometre trenches, will be made in German coastal waters.

Operations follow the award-winning ‘green logistics’ concept of the pipeline’s predecessor, Nord Stream, which is based on using low-emissions transport. To minimize the environmental impact of moving the heavy 24-tonne pipes, routes are kept as short as possible on each leg of their journey to the seabed.

The logistics HUBs have been strategically positioned along the pipeline route so that pipes can be shipped to the pipelay barges from the closest port during construction. Around 200,000 tons of CO2 can be saved in the course of the project thanks to the optimized logistics.

EUR 10,000 mln economic benefit for the EU

Because of the complexity and multitude of financial layers that multiple value chains are generating, every consequent phase of the project is adding to the value of the original activity thus creates a ripple effect which is difficult to be précised or evaluated. For every sector affected by a specific activity, such as the investment in pipeline, a dam, a bridge or new plants, there will be several ripple effects, sometimes in sequential steps, triggering value creation in other sectors.

The total economic benefit created for the European Union, receiving 58% of investments, is nearly EUR 10,000 million, creating close to 60.000 full-time equivalent jobs, and adding nearly EUR 5,000 million in GDP on an overall basis.

To classify the impact waves, we can break it down to:

- Direct effects, which include all activities directly related to the event in question;

- Indirect effects, which include all suppliers of goods and services to the direct activities;

- Induced effects, which consist of the household spending that results from the salaries and wages earned in the first two categories.

This represents the flow of investment from the project to each country. The totals have been used to model the economic impact for the top 12 countries affected – Russia, Germany, the Netherlands, Finland, Switzerland, Sweden, Austria, the United Kingdom, Denmark, Belgium, Italy, and Norway. Committed and spent funds in these 12 countries make up 97% of the total funds committed in the long-term business plan of the project.

Apparently, the effects can be different depending on the economic/industrial structure of the country examined and the relative cost of labour. For example, within the EU, any investment will have a larger impact in Greece or Spain (which has a lower relative labour cost), than in Germany or France. Equally, the results in Russia can be expected to be much more significant; more specifically, every euro spent in investment will create three times more full-time equivalents in Russia than in Germany.

Estimated Overall Impact per Country

- The overall impact on the Danish economy is equivalent to an economic output of nearly EUR 300 million, adding EUR 160 million to GDP and creating 1,580 jobs.

- The overall impact on the Finnish economy is equivalent to an economic output of nearly EUR 900 million, adding more than EUR 410 million to GDP and creating 4,500 jobs.

- The overall impact on the German economy is equivalent to an economic output of more than EUR 3,850 million, adding roughly EUR 1,850 million to GDP and creating roughly 24,000 jobs.

The investment does not cover the connecting infrastructure nor the compressor stations required after landfall – these will be undertaken by separate organizations and are not included in the Nord Stream 2 project. These additional investments will have further economic beneficial effects on the German economy that are not reflected in this calculation.

- The overall impact on the Dutch (Netherlands) economy is equivalent to an economic output of EUR 2,389 million, adding roughly EUR 1,050 million to GDP and creating 11,990 jobs.

- The overall impact on the Swedish economy is equivalent to an economic output of EUR 635 million, adding nearly EUR 350 million to GDP and creating 3,270 full-time equivalents, spread over many different sectors.

- The overall impact on the Russian economy from Nord Stream 2 is equivalent to an economic output of more than EUR 6,100 million, adding nearly EUR 2,700 million to GDP and creating more than 144,000 jobs.

The investment does not cover the connecting infrastructure or the compressor stations required – these will be undertaken by separate organizations and are not included in the Nord Stream 2 project. They will have additional economic beneficial effects on the Russian economy that are not reflected in this calculation.

Geopolitical Gambits

Depending on who you ask, Nord Stream 2 is either a sustainable way to ensure European energy security or a proxy for Russian hybrid warfare. Or both.

The official objective of the Nord Stream 2 project is to provide additional means for safe and secure supply of gas to Europe. Europe’s dependency and supply gap are raging, due to growing consumption, depletion of indigenous reserves, and phasing out of nuclear and coal-fired power generation capacity.

The project has been surrounded by controversies since its inception. One of the primary actors in this play has been Ukraine, from the very beginning. Ukraine filed a lawsuit with the Energy Community Secretariat seeking action against the pipeline. It also appealed to the European Commission to terminate the gas project as it is against the country’s strategic interests. The route of the pipeline will provide a circumvention of Ukraine, which stand to lose high-transit fees. Ukraine has been obviously benefitting for a long time from its ‘middle man’ status, as it has been the energy gateway of Russia towards Europe. The Baltic Sea offers a short, direct route from northern Russia to northwest Europe, thereby decreasing costs, increasing stability and theoretically increasing security of supply. Notably, it also enables Russia to bypass Ukraine, and maybe ‘strangle’ it; this move is depriving Kyiv of the valuable energy transit fees and allowing Moscow more flexibility to use energy as a leverage point with Kyiv without broader European impacts. Given the fact that we still face a rather awkward ‘occupation’ of Crimea by Russian forces after the invasion of ‘little green men’, and the ongoing civil (?) war in eastern Ukraine, this will further weaken the country’s capacity of positioning itself strongly towards Russia.

Another strong player in this geopolitical game, Poland, believes that when Russian gas no longer passes through Ukraine, the country will no longer be guaranteed protection against further aggression from Russia. According to Kay-Olaf Lang from the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Warsaw also sees the Nord Stream 2 pipeline as a symbol “of German disloyalty towards its eastern neighbour, and of a special relationship with Russia.”

While German chancellor Angela Merkel and others have insisted that the status quo of gas flow must remain, no specific measures have been taken towards that direction and Russia remains unreserved about its intentions to restrict gas supplies once the new pipeline is complete. The CEO of Russian oil giant Gazprom stated that gas will continue to flow via Ukraine, “but the volumes of such transit will be much lower, probably, 10 to 15 billion cubic meters a year.” That’s just 15% of the gas currently in transit, and this comes amid speculation that Russia intends to eventually reduce this number to zero.

Additionally, the governments of ten European countries declared their opposition to the project through a letter to the European Commission stating that the pipeline project is against the interests of the EU. The countries involved are Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. Many southern pipeline projects are apparently endangered with being obsolete even prior to their deployment due to Nord Stream and that means too much conflicting interest.

When it comes to the Nordic situation, there are concerns about dangers of letting Nord Stream workers to use Swedish ports, including their main navy base in Karlskrona. Allegedly, that could enhance Russia’s capabilities of opportunity to “gaining intelligence and plotting espionage activities”. Other analysts warned that the pipeline gives Russia the pretext to increase their military presence in the Baltic Sea, even using it as a means to transmit military information on the movements of naval vessels.

Namely, Denmark who is one of the significantly involved countries in the project has yet to validate the licenses for the pipelines, without providing arguably good reasons. The Danish Energy Agency still cannot estimate when an authorization would be issued. Despite this situation, Nord Stream representatives still claim that the gas pipeline will be ready by the end of 2019, even if the obstacles raised by Denmark delay the operations.

Not a long time ago, EU energy commissioner Miguel Arias Cañete actually stated that Nord Stream was not in the interest of Europe as a whole. The Commission isn’t openly trying to block the pipeline project, but it does want to make it an EU project, meaning it would be subject to strict EU competition rules. This possibility is much closer today, and not just in the horizon, and can further complicate the situation.

Any such decision would require the agreement of the European Parliament and the European Council of member states. The Commission has Poland and the Baltic countries on its side, as well as Britain, Denmark, Slovakia, Ireland, Sweden, Italy, Luxembourg and Croatia. Germany, Austria and the Netherlands, on the other hand, want to proceed with Nord Stream 2, preferably in its current form. Businesses from these countries are involved in its construction.

One deciding factor could be the official stance adopted by France. France has been traditionally keen on supporting Germany, and would arguably stand behind its energy supplier, Engie, which is also involved in the Nord Stream 2 project. It’s therefore likely that Paris will support Berlin. If Paris votes against applying EU common rules to the project, or if it abstains, the Commission will fail to achieve the necessary majority. Romania, which currently holds the presidency of the European Union, is trying to broker a compromise, but time is running out.

Blocking Nord Stream 2 does not seem realistic for now, but its opponents have been moving from strength to strength. Kay-Olaf Lang says that “Warsaw has succeeded in putting a project on the political agenda that for a long time was regarded as purely economic”. He comments that the opposition to Nord Stream 2 has contributed to it becoming an important element of the geopolitical discussion, not only in eastern Europe, but in Germany, too.

And as if the European playground was not crowded enough, there are also the Americans who wish to play. Congress has been threatening to target strategic European partners with new legislation that would impose sanctions on key allies. The Protecting Europe’s Energy Security Act would mandate sanctions on those involved in the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project.

Texas Republican Ted Cruz along with other senate members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, drafted the act to increase pressure against Russian interests and one of its most important exports. A draft version of the bill targets vessels that lay the pipeline and would also deny visas to executives from companies linked to those vessels. It also would block transactions in U.S. based property or interests belonging to those individuals and would penalize entities that provide insurance to the project. Specifically, the Act mandates blocking (asset freeze) sanctions on those involved in the sale, leasing, facilitation, or provision of the vessels used in the undersea construction of Russian energy export pipelines at 100 feet below sea level, including Nord Stream 2.

While these measures may seem like a technical sanction aimed at Russia, the potential targets are actually major European companies including Germany’s Uniper and Wintershall Holding, Engie of France, Austria’s OMV, and Anglo-Dutch Shell. Since Russia does not involve in deep-water project technology it relies on European contractors.

The U.S. president was not less direct: “If you look at it, Germany is a captive of Russia, because they supply – they got rid of their coal plants, got rid of their nuclear, they’re getting so much of the oil and gas from Russia,” Trump said in July of last year at the start of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s annual summit. “I think it’s something NATO has to look at.”

Interestingly, there is no alternative offered. As it stands, U.S. gas is much more expensive than the Russian, due to transit and logistics costs. While the U.S. rate does provide the EU with leverage with which to negotiate with other gas suppliers, it is not enough.

The only really sustainable approach on behalf of the EU, in accordance with the energy supply diversification dogma, lie southern. The EU is already expanding its current energy framework, and also developing new capacities in the Adriatic Sea (on Krk island, Croatia), in the Baltic Sea (in Poland), and in the Mediterranean Sea (in Greece & Cyprus). These new and expanded projects, faced with their own complicated geopolitical challenges, may allow for a significant increase of domestic liquefied natural gas for the EU.

Conclusion

The starting and ending point of this article remains the fact that Nord Stream 2 is one of the potentially most beneficial and still most scrutinized ongoing projects in the energy sectors. It has the capacity of offering Europe (Germany) a stable flow of gas, avoiding high costs, environmental threats and warzones (Ukraine); it will also a have huge beneficial financial impact for all parties involved. There is a big BUT here though; the major party involved is the Russians and the shirtless ghost of Putin, riding a bear, still hovers over Eastern Europe and taking its toll on Nord Stream 2.

On top of that, this project will rain on the parades of South Europe, where similar and very promising projects are being planned or developed. Afterall, the rest of the Europeans have a right in their claims over a piece of the energy pie.

On the other side, the Americans do not seem to be very happy with the evolution of the project or Gazprom’s good (?) intentions. They will pursue aggressive measures against the project even if that means that they hurt their European partners; after all, the Trump dogma has been unforgiving towards the traditional allies from the beginning.

At the end of the day, the Nord Stream story goes back several years proving to be financially sustainable and all parties have strong, deep, interwoven interests in continuing (namely, the ex-chancellor, Gerhard Schröder, who is currently the chairman of the board of Nord Stream AG).

The rest of the Europeans, along with the Americans have just started scraping of the surface and will continue to do so. Until they hit bone, and as long as there is no better alternative, money talks and business will continue as usual.