Europe’s New Bet – Geothermal Energy

Like a gambler never satisfied by the past and present gains, the European Union (EU) makes a new bet in the energy sector – geothermal energy. Or, more accurately said, in the sector of environmental protection and the definitive abandonment of classical sources and ways of producing energy. Progress, some would say, damnation, would others say. The fact is that, with each such bet, there are many losers and few benefit from the gains. Usually, those who lose must also pay fines to Brussels.

Year after year, the European Commission (EC) pushes it a little further and imposes, as an effect of alleged tough, but honest negotiations between its extremely disparate members, new targets in terms of share of renewable energy in the final energy consumption of each Member State. Some flagship states of green energy, such as the Netherlands, Finland or Germany, are those that come up with the most ambitious plans, and all these desires of a minority become an obligation imposed on the majority.

10-15 years ago, wind energy was seen as the saviour of the planet, and therefore, as both target and conclusion, all EU members were forced to adopt it. The famous 20/20/20 third, which meant a 20% reduction in EU greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990 levels, a 20% improvement in energy efficiency and ensuring that 20% of energy consumed comes from renewable sources (wind, solar, biomass) is about to materialize.

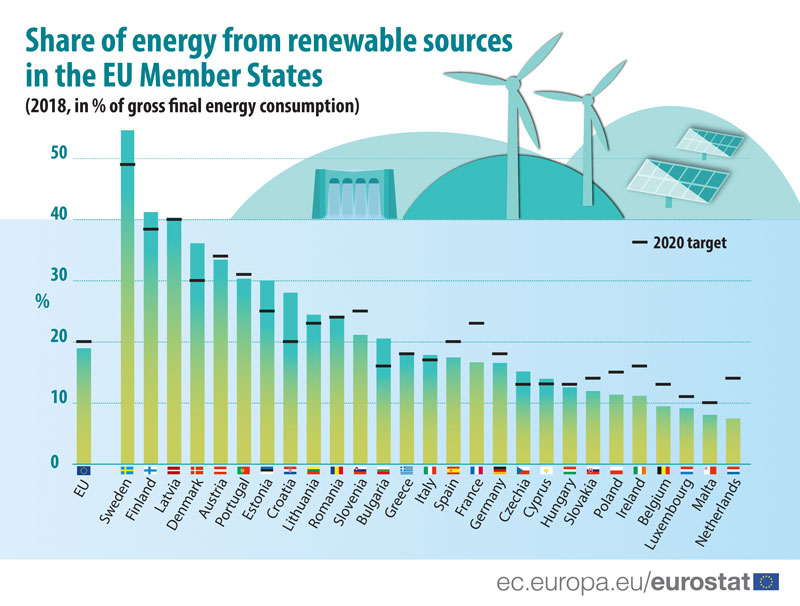

According to EC statistics, energy from renewable sources accounted for 18.9% of energy consumed in the EU, so very close to the proposed level. Whether this level is reached or, who knows, exceeded, we will see most likely next year.

In the meantime, more than half of the 2020 has already passed, and the EU has set other objectives, even more ambitious than the famous 20/20/20. Therefore, the new target, included in the European Green Deal, meaning for the year 2050, should represent an EU released from the yoke of polluting energy sources, such as coal, or, as it is increasingly felt at the level of the Community political sensitivity, natural gas. Nuclear power is already an outcast. At the time, the EU shouldn’t, according to politicians in Brussels, emit any molecule of greenhouse gas, and this would be obtained through a number of strategies which, if they are also implemented, will radically change especially how we produce and consume energy in the EU. The main industries to be impacted by these European aspirations are that of the energy production and automotive, the latter being overwhelmingly remodelled into a socialism of mobility by the fact that holding a car will become a rarity.

And, because this transition from coal to wind and solar power to whatever energy source will be considered non-polluting and trustworthy (from a political point of view) at the level of 2050 will make victims in everything that means economic life, the EU will provide a financial support of EUR 100 billion and technical assistance during 2021-2027 to help the citizens, companies and regions that are most affected by transition to green economy. What will these regions be? Definitely those in Central and Eastern Europe, where countries such as Romania, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria or the Czech Republic are still dependent to a great extent on coal and natural gas. In fact, Romania is only starting to discover natural gas, metaphorically speaking, given the little use for this resource, which it has almost in abundance.

One of the smaller ambitions (small probably due to the lack of significant reserves of raw material) of the EU are directed towards geothermal energy.

In a project called Geothermica, which involves specialists, analysts and financiers from 13 countries, the EU throws in a budget of EUR 30 million for small and large projects using geothermal energy for heating, cooling and electricity generation. Like the wind, the boiling water from the ground would have the potential to contribute to the ‘greening’ of the air we breathe. As in the case of any other energy source considered, for various social, economic and especially political arguments, as ‘saviour’, geothermal energy is still dressed in the in the garb of non-polluting righteousness. But, in terms of geothermal water, the EU does not hold such substantial reserves as to witness a new gold rush, as it happened with wind energy. However, this resource is already used in the EU, even if by few Member States, and rather experimentally. Maybe this is precisely what the EU wants to correct?

If the EU expects to create trends globally, in various economic sectors, in terms of geothermal energy it could be said that it rather learns from others, because geothermal energy is not a novelty for other countries on other continents. Because, while the EU only now discovers geothermal energy, other countries, such as Kenya or Morocco, have done it a long time ago, since the eighth decade of the last century.

At global level, the public figures show that geothermal energy could generate up to 8.3% of the electricity needs. Moreover, if this energy were to be used to the maximum, 39 countries in Africa, Central Europe, South America and the Pacific could cover entirely their electricity needs.

The world leader in the use of this type of energy is the US, which, with an installed capacity of 3,639 MW (about half of the production capacity of Hidroelectrica, the largest electricity producer in Romania), produces 16.7 billion kWh per year (about as much as Hidroelectrica produces in an average hydrological year).

Ranking second, but with chances to overtake the US, is Indonesia, with an energy production capacity from geothermal sources of 1,948 MW, followed by the Philippines, with geothermal plants of 1,868 MW in 2018.

Next in line are Turkey, Mexico, New Zealand or Japan.

The few European states that fall into such a ranking are Iceland or Italy, with almost 1,000 MW, the leader of the EU bloc in this respect. Germany also has a number of intentions to use this type of energy, but for now at small scale, with existing units of less than 40 MW, while Portugal holds 30 MW in geothermal energy. The geothermal energy installed in the EU can supply about 2 million homes.

In other words, the EU is very poorly represented in this hierarchy, and for things to put the Union in an even less favourable position, many of these power plants were commissioned in in 1981 (a power plant in Kenya), 1984 (Mexico), 1994 (Indonesia) or 1996 (the Philippines).

Geothermal energy is certainly not a missed train for Europeans, but it is clear that it is not a pioneering industry. Or, a term more appropriate for the civilizing claims of Brussels, a missionary industry.

But there are also other states that hold such geothermal resources and are starting to invest in their use. An example is Ethiopia, which, in the first half of this year, signed an agreement to contract a loan of USD 10mln for an investment in a geothermal power plant with a power of 50 MW. The plan would be operational in 2024.

Taiwan has also signed an agreement with Swedish energy technology company Climeon for the construction of the country’s first commercial geothermal power plant.

Globally, in 2019 there were almost 370 units producing energy from geothermal sources, totalling a production capacity of 15,406 MW. New geothermal projects brought last year 759 MW in addition to the global installed capacity, this being the largest annual growth of the installed power in the recent years, a similar level being recorded in 2014.

It remains to be seen how the political class in Brussels and each national government will turn geothermal energy, which is not an extremely rich resource on the Old Continent, into a probable obligation whose non-compliance will, according to already known models, be punished by fines and in the mainstream media, as with the star of renewable energy, the wind.

Romania is one of the countries that have this resource in their energy portfolio. Moreover, Romania holds, in various proportions, all energy sources, both polluting and revolutionary clean, but, nevertheless, has become a net importer of energy in the last year. As we are already accustomed, Romania has little of everything. Including geothermal energy, which it has been using since before the politicians in Brussels negotiated new definitions of green energy and new ceilings of clean energy in the final consumption of each Member State.

Geothermal energy in Romania

In Romania, research has been conducted and wells have been drilled in search for geothermal water sources since the 1900s, and the conclusions are that such reserves of geothermal waters are found in the west, in Bucharest and in Dobrogea.

There are already two localities, Oradea and Beius, that use this resource. Moreover, Beius is the only city in Europe, except for Island (the richest country in this resource), which uses geothermal water entirely in the district heating system.

Because I mentioned Iceland, this country uses geothermal water to heat 90% of the almost 400,000 inhabitants, a performance due to the unique specificity of the basement of this island state. The installed power of this country in geothermal power production facilities is about 800 MW.

The city of Beius, Bihor County, is the only city in the country where district heating is exclusively based on geothermal water. In Beius, geothermal water used to heat over 100 blocks of flats and several public institutions is extracted from depths of 2,500 – 3,000 meters by two wells and is delivered to consumers through a system of 17 kilometres of pipelines. According to information from Transgex, the operator of the heating system in Beius, a third well reinjects into the ground the thermal wastewater. The two wells extract annually over 420,000 cubic meters of geothermal water, the equivalent of 17,000 Gcal, at temperatures varying between 70 and 84°C.

In Bucharest, a city that is said to be on a geothermal water lake, discussions on the exploitation of geothermal resources have existed since at least 2009. At that time, geothermal water was used in a swimming pool at the Press House (which no longer exists) and to heat the Ana Aslan Institute.

The subject of geothermal water reappeared in 2013, but again without any real effect. However, Beius is not the only place in Romania where the potential of geothermal waters is used, active projects already existing in Oradea (where an entire neighbourhood is heated with this resource), Bors, Cernavoda, Olt Valley, north of the Capital or some hotels in Calimanesti – Caciulata. Probably the most well-known use of geothermal water is the one at Baile Felix (now in ruins) or the Therme Bucharest complex (expanding).

In other words, geothermal energy is not a novelty for Romania, but its use is not part of a national or at least regional strategy, but was the result of independent initiatives independent of the government. And an initiative assumed by the government on the exploitation of geothermal water does not exist at this time, although this resource has been vaguely mentioned in multiple attempts at national energy strategies. But it will certainly exist from now on, once the EC has turned its eyes to the Community basement.